2012.07.01

Following the Basic Workshop that took place on June 3rd, Mr. Oriza Hirata held a workshop on practical application. In addition to the TOBIRA candidates (TOBIKO), museum curators Ms. Inaniwa, Ms. Sasaki, and Ms. Tamura joined this time.

Scripts were distributed right away, and TOBIKO started acting. The scene is set on a train, where a male and a female were traveling, sitting facing each other in booth-like seats. While they are chatting casually, another female appears and asks to sit with them. They cheerfully allow the woman to sit, but their fake conversation and smiles continue. We can say that the three of them were having an awkward moment.

The TOBIKOs tried their best at acting while reading the script for the first time.

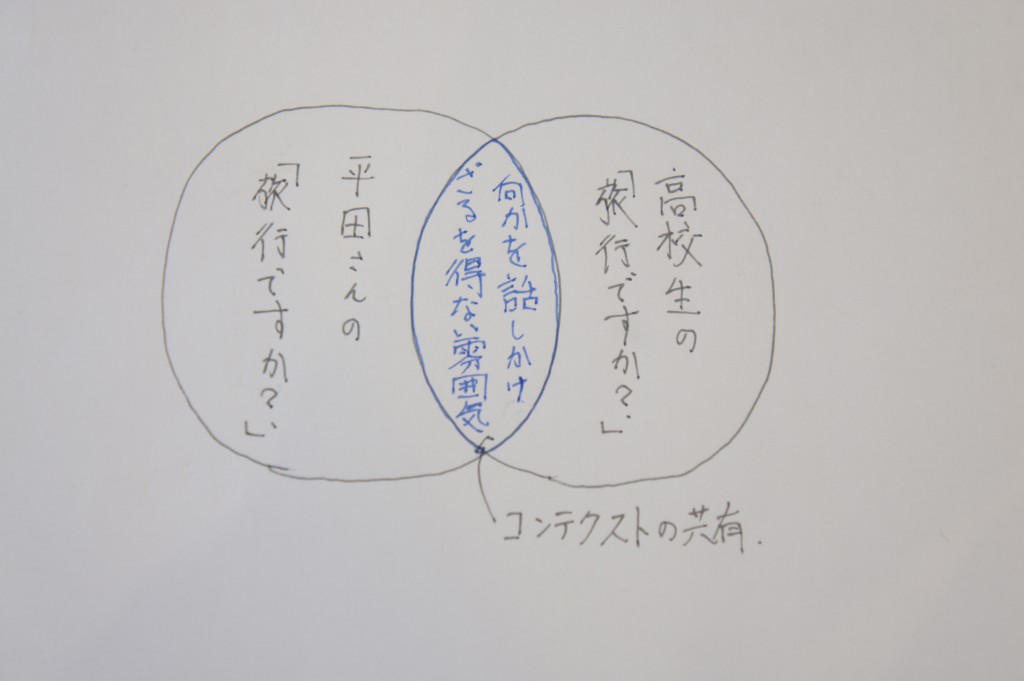

After acting out the script once through, Mr. Hirata explained the objective of the workshop. Once while doing this workshop for students in Drama club at a high school, one of the lines, “Are you on a trip?” surprisingly did not come out naturally. Mr. Hirata asked the high school students as to why their delivery of the line sounded so awkward. The answers that he got were “I have never struck up a conversation with a stranger on a train,” or “I cannot really grasp what it would be like, since I would never talk to a stranger like that.” Understandable. Mr. Hirata had an expectation of actors who could understand the subtle context of a scene featuring three people sitting together. However, it seems like high school students who had never experienced saying, “Are you on a trip?” could not understand the context of the lines.

Mr. Hirata explained that this situation is caused by the “context gap.” Essentially, this means that even if you understand the meaning of the words, there is a gap between the context of the words due to each individual’s living environments and cultures, yet the conversation continues on. However, these context gaps are quite difficult to notice in conversations. And Mr. Hirata pointed out that continuing a conversation without noticing this context gap is the biggest cause of communication failure in many cases. (No matter what kind of job you have, most complaints from clients can be attributed to this “context gap.”)

Incidentally, Mr. Hirata also held the same workshop for local college students in Australia. When he asked the students “Would you talk to someone that you just met for the first time in the train?” They responded, “It depends on their race and ethnicity.” When he offered the workshop in Ireland, everyone responded that they would talk to the strangers. In addition, when dealing with upper-class British people, initiating a conversation randomly without being introduced would be considered bad manners.

What was most interesting in Mr. Hirata’s explanation was that, in the world of theater, the playwrights and directors know the functions of these contexts inside and out. So it is possible to convey completely different meanings by cleverly altering the context of the performance, even if the lines are the same. Let’s suppose that a man who initiates conversation with “Are you on a trip?” was a British aristocrat, and then we’d be utilizing a different context; now the earlier picture of a man awkwardly talking to a stranger is quite different. It is possible to induce the audience to see different views. There is the previous example where the man was awkwardly talking completely changes into a “man who knows no manners” or a “scene where an attractive woman appears, making you want to forget about all manners and talk with her.” From these examples, it is clear that the “context” of a conversation is more important than the meaning of the words.

If that is the case, I felt that the ability to understand the “context” is necessary for any art communicator. According to Mr. Hirata, people typically represented as people who are disadvantaged in society, for example, children. They oftentimes talk based on context rather than meaning of words. For example, let’s say that there was a child who ran home in excitement and said, “I didn’t do my homework for today, but my teacher didn’t get mad at me!” At first glance, it sounds like the subject was about the child not doing his or her homework, so you would want to scold him/her. But actually, the child might have wanted to happily convey their appreciation of the teacher’s generosity, or how they really like the teacher.

When you think about this, it can be understood that the ability to understand the context of those who are disadvantaged and cannot speak logically (such as children) is even more so needed from those who support them (such as teachers and parents). In this regards, Mr. Hirata expressed hope that, rather than the ability to speak logically and critically, which was the previous emphasis of Japanese leadership education, future leaders gain the ability to read the context of those who are disadvantaged in society and understand the context of people who cannot logically express themselves.

This ability to understand context is expected to play large role in the medical field as well. Nowadays, modern medicine has become so advanced that the implications of treatment are more diversified than ever. It will not be possible to provide true treatment to patients unless you understand the patients’ needs – whether they want to live a mere second longer or spend the remaining time with their family. Also, understanding the context in daily nursing case is very important. When a patient complains about their chest and says, “My chest is in pain,” a good nurse will respond to them by calmly repeating what the patient has said – such as, “Your chest is in pain, right?” By repeating what they have said, it sends the signal that “I am here with you,” or, “I am focusing on you.” In this scenario, by understanding the patient’s context and letting them know that we have received their feelings and thoughts, we establish a basis of communication in the medical field.

However, these behaviors are not that complicated – it can be said that everyone already has the fundamental communication skills, and intrinsically, we use them in our daily lives. However, as Mr. Hirata points out, even if we each have high communication skills, it is easier for failure to occur in places where external factors may interfere with the context of their message, such as: in a hospital where people may panic easily; in the business world where there are numerous time constraints; and inside of a small research lab with a strong hierarchy. This can potentially lead to trouble in the organization. Therefore, individuals simply having the ability to understand context is insufficient. It is imperative to seek out the ideal forms of various communications by having multiple views that include external factors. For example, is a doctor’s seating arrangement conducive to talking easily with his patients? Or in a business environment, is the meeting room designed for a sense of openness?

Then, these ways of perceiving without directly connecting the cause and effect are called “complex systems.” The new academic field called “communication design” looks at problems in communications in complex systems. More precisely, there are many things that the TOBI Gateway Project will have to take into consideration, such as whether an environment suitable for good communication is set up or not.

Let’s go back to how the high school students could say naturally the line, “Are you on a trip?” Even if high school students who do not have much life experience are told to think about the line “Are you on a trip?” it would probably be impossible for them to understand the context hidden within the line. Instead of practicing the line “Are you on a trip?,” it is possible to teach them the context of the script by combining the high school students’ life experiences and the context surrounding the lines to make them think of the type of atmosphere where it would you must strike up a conversation. Oftentimes people say that a convincing performance is created when actors either become the characters or inhabit a different personality completely. Even professional actors and actresses expand their wings by embracing the parallels between their own life and the character they are portraying, and determining how the character would be if they were to strike up a conversation, even if the actor himself would not normally do that.

In order for us to understand the behaviors and values external (other people) to our own context (internal), you must first look for the shared parts of both parties’ contexts and expand the shared parts of the external (other people) context more and more. In recent years, this method has been gaining more attention in the education world as well. It is thought that role play has been advocated as a way of dealing with problems, especially bullying, going from a “sympathy-oriented education to an empathy-oriented education.”

With the meanings of “from sympathy to empathy” and “from uniformity to communality,” instead of simply sympathizing with bullied children, this is a method which attempts to resolve these issues by involving the bullied children’s feelings and finding commonalities (empathy) with as many children as possible while increasing the commonalities of the “emotional pain” even just a bit.

When you think about it, it feels like communication is achieved by seeking out the overlapping aspects between your own context and another person’s context. When there is a person we want to speak with, we seek out commonalities and try to expand them. The more things we have in common with the other person, the more likely we also enjoy the communication. This workshop touched on the importance of understanding the context of others, which is truly the starting point of communication.

The objectives of Mr. Hirata’s workshop were so intriguing that I almost forgot it was a workshop. Now let’s get back while keeping the original point in mind. The TOBIKO students were given an assignment to act out the line “Are you on a trip?” as naturally as possible. They had to find a way to create a situation where you would have to strike up a conversation and make the line “Are you on a trip?” flow more easily by adding 3-4 lines before it. This is a method where the actors themselves create context in the scene, so that they could personally understand it themselves. These 3-4 lines of the script are like the projection lines that you draw in geometry diagrams: you can use them to help you solve the problem and you can erase the projection lines later, if you can solve the problem well (or speak better).

Woman: (Makes a strange facial expression)

Man: “Ah, the dinosaur…”

Man: “It’s been here since we got here…” (Trying to show that it’s not theirs)

Woman: “….” (Awkward atmosphere)

Man: “Are you on a trip?”

It is quite a bit of a stretch, but it is an interesting example (laugh). At this point, the students were put into groups of three, and each group took turns performing their skit after discussing about how to make the line “Are you on a trip?” easier to say by adding 3-4 lines beforehand. They were given about 30 minutes to discuss. They worked very hard within the given amount of time, but the assignment was more difficult than it seemed. Once each of the lines was decided upon, each group performed their piece. It was quite entertaining with endless ideas (laughs) – one group asked “Would you like some red bean buns?” prior to the line “Are you on a trip?” Another group set the scene where suddenly the “Tower of the Sun” [a famous exhibition of the 1970 World Expo in Osaka] appears outside the window and after an exclamations of “Wow!”, someone asks, “Are you on a trip?”

After each group had finished their performance, Mr. Hirata’s made comments about each one. However, through understanding the context surrounding “Are you on a trip?”, we realized that there is a vast difference between reading the lines with feeling and performing the lines we struggled to come up with.

Once the performances had finished, Mr. Hirata concluded his workshop, which had mainly focused on communication, with a lecture on “the role of arts in society,” where we discussed the meaning of museums and theaters as social devices. Below, I will introduce Mr. Hirata’s lecture while including my own explanations.

According to Mr. Hirata, before thinking about “how museums and theaters should function in society,” we must first re-think about the environment in where they are located. If you look back, because of the recent expansion of large suburban supermarkets in the provinces, it has become possible to get good products at good prices all year round. The more rural the area, the more shopping districts become deserted since they are so easily influenced by market competition. Bookstores and electronics stores are disappearing, as well, and Mr. Hirata contends that you will see the same scenes all over Japan no matter where you go. In order to compete against the large stores that have a high cost performance, regional family-owned stores are forced to focus on cost-effectiveness and can no longer afford to allow any waste. These days, small art galleries, photo studios, and even places for children to gather like mom-and pop candy stores are disappearing. In contrast, large cities like Tokyo and Osaka still have strong consumer activity, and therefore, used book stores and jazz cafes in shopping districts can still survive. At a glance, large cities may seem to be busy and bustling, while the countryside has an image of being laid-back. However, there seems to be a big gap between this perception and reality.

You can no longer rely on the owner of a used bookstore to foster the growth of literary youth. Mr. Hirata points out that, in conjunction with a delay in government response, the cultural gap between cities and the countryside is increasing, as well as a big difference in competitiveness.

What is more problematic is that in the countryside, where there is no longer room to allow waste, people who are societally disadvantaged, such as the homeless or school dropouts, now have no place to go. Some of these people will drop in to a karaoke booth or a convenience store, and homeless people may head to local libraries. In recent years, there was a distressing incident where a homeless man who scolded rowdy junior high school students in a library was beaten to death. Mr. Hirata says that, in order to avoid incidences like this, society must frame itself in a way that allows anyone to participate easily, even if you are societally disadvantaged.

Mr. Hirata proposed the idea of “social inclusion” to address these problems. While adding my own explanation to the concept of “social inclusion,” my understanding is that we should lend our hands to those people who, for whatever reason, are (or may be) socially isolated due to unemployment, poor health, old age, or mental instability in order to help them reintegrate into society. This will create a society that doesn’t isolate people. By recognizing and respecting each other’s existence, and by gradually building a supportive community, we aim to build a safety net against the confusion in the event of a solitary death or disaster.

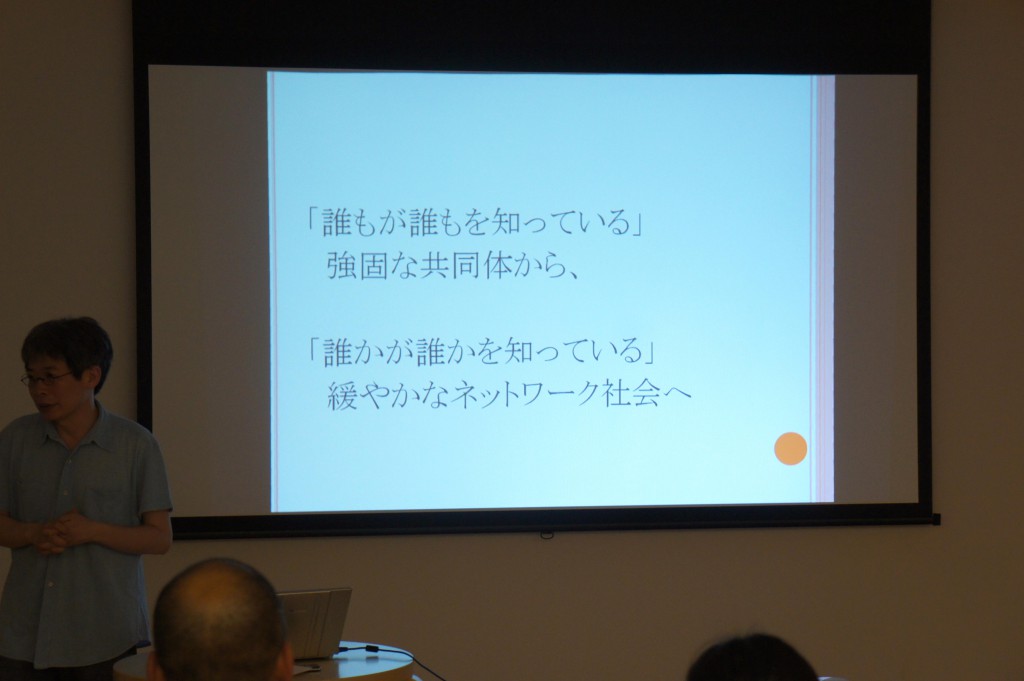

According to Mr. Hirata, pre-war Japanese culture created a society where they planted and harvested rice together and everyone knew everyone else. However, recent generations dislike feeling obligated by strong collective organizations to do things such as joining the local chamber of commerce, or taking part in all local events such as the Japanese Bon Dance in the summer or the festivals in the autumn. In addition, it can be said that most people’s human interaction and activities are more limited to their commute between their home and school or work place, and there are fewer places where they can retreat into a mental safe haven. This is creating an environment in which modern society people can easily isolate themselves even more. In order to respond to these issues, society needs a “third place” suited to modern society that can come also withstand market principles which is not school, or your workplace, home, karaoke box, or convenience store. Mr. Hirata said that these third places could possibly be museums, music halls, libraries, theaters, or basketball courts, for example. People oftentimes say that museums and theaters are extraordinary spaces. Not “out of the ordinary” (as in, say, a haunted house), but extraordinary, as in a place where people who would most likely not meet otherwise according to economic principles will be able to meet each other despite their differences.

Mr. Hirata points out that there is a need to change Japanese society from an “everyone knows everyone else” type of strong collective entity to a “someone knows somebody” type of Loose-knit Network Society, by providing the opportunities to create connections with other people who come to these extraordinary spaces wherein everyone is on equal footing. For example, “That grandpa seems grumpy, but when he participated in volunteer activities, he was amazing.” or “That Brazilian guy looks tough, but he is great when he teaches soccer to kids.” Now museums and theaters are getting more and more attention as societal devices to support a “someone knows somebody” type of Loose-knit Network Society.

Mr. Hirata continued on and introduced us to the cases of social inclusion in post-’80s museums and theaters. After the ’80s, people in the West emphasized the revival of cities by setting up art centers to easily integrate various minorities into local culture. It is said that the art centers were built from the design stage based upon the users’ opinions as to what kind of environment would be needed for the creation of a place for societally-disadvantaged people, such as Hispanic and Chinese immigrants, single mothers, the disabled or elderly, to easily become a part of society through arts. In Japan, sometimes voices of residents are heard, but it is very difficult to integrate the voices of these end-users’ voices when most of the plans are made by people with power or education. Also, it is important for the socially powerful people, like town assembly members and CEOs to participate in the process at the same time. We need to create a system where those people’s power can be returned to society through theaters and museums. The cultural facilities in Japan are not yet there, however.

Also, a typical example of “social inclusion” in the West comes in the form of Homeless Projects which provided opportunities for the homeless to take a shower and go see a show. Homeless people in developed countries are typically not homeless from birth, so many of them have dropped out of society from some reason or another. We hoped that they will get back the stamina to survive by being exposed to artistic things they may have previously enjoyed. They may reminiscence, “When I was a kid, I used to go to concerts with my mother….” “Oh, I used to like the opera…” If this could give them the motivation to work, it will be a very cost-effective method for the government to help prevent homelessness.

In contrast, if you prepare meals for them – even though it could save their lives – it will not be radically prevent homelessness. This is because the majority of the reasons people become homeless are mental. Of course, there are economical reasons as well. But if it were solely economical reasons, they could get social welfare, so there must be other reasons that they became homeless as well. There is a need for some type of psychological care for them in order to resolve it, and Mr. Hirata says that art plays a big role.

It is said that, even in Japan, there are examples of social inclusion through arts. One of the most well-known examples is when daily workers in Kamagasaki, Osaka and homeless people collaborated to create a picture story theater group and performed together at places such as retirement homes. Recognizing that they are contributing something to society positively affects their emotional well-being while increasing their motivation to work, which may help them grow enough to attend the Edinburgh International Festival.

Also, the “Komaba Agora Theatre,” which is owned by Mr. Hirata, has offered a huge discount of 70% off to recipients of unemployment insurance for the last few years. This measure is widely implemented in European theaters and museums, but is not yet implemented in public halls in Japan. In the past in Japan, people probably thought that unemployed people going to see a show at the theater implied they were neglecting their job search. When the economy was booming, anyone could find a job within six months and there was a strong impression of the unemployed being lazy. However, the economic situation is not the same anymore, and unemployment is beyond our own responsibility now. Becoming unemployed regardless of how hard you work can cause a chain reaction of “social exclusion” (due to unfavorable factors from your past, like unemployment, divorce, illness, etc. can accumulation and create a connection to “social exclusion” outlook: leading to lack of a place to live and social relations, and not becoming a part of society). Thus, it can be said that we are living in an environment which has of high possibility of becoming isolated from society. We live in an environment that is easily prone to “social exclusion” based on economic principles. And thus, “social inclusion” that mainly revolves around “extraordinary spaces” such as museums will effectively function as a countermeasure.

Mr. Hirata’s concept of using museums as the “third place” is precisely in line with some of the philosophies of the TOBI Gateway Project. (The philosophy of the TOBI Gateway Project is explained in “Bringing out the Community through Art (at The University of Tokyo).” However, the biggest difference between the structure of the TOBI Gateway Project and the structure of Mr. Hirata’s “social inclusion” is that the TOBIRAs are highly skilled and select elites in society, and their community shares a wide variety of values by intelligence, so they do not include societally disadvantaged beings who need social inclusion. However, it is possible to approach the concept of “social inclusion” by thinking of how we can create a gateway between the museum and society by returning the power of museums back to the society by taking TOBIRAs’ individual skills into the equation. For example, it is possible that numerous workshops and seminars created by TOBIRAs – not only the regular museum programs – may become the motivation for people with differing values to begin visiting museums. Then, by having many people participate in these programs, it may facilitate the creation of a “somebody knows somebody relationship.”

Mr. Hirata said that, according to statistics and surveys, people will travel within a 30-minute drive without stress, as long as there are events like advanced art and cultural activities, environmental protection activities, or sports events in which they want to voluntarily participate. Therefore, there is no problem with developing a broad range of programs. But instead there is a tendency for people to only come to things that they are interested in, so it is important to have various interests in mind when building communities.

Mr. Hirata introduced us to an example where people who are participating in local communities shared ideas. Through creating several entrances (gateways), they could effectively create a link with the outside people who have a variety of values. In the Tenjinbashi-Suiji Shopping District in Osaka, there is a Rakugo theater called “Tenman-Tenjin Hanjoutei.” Since Hanjoutei seats about 200 people per show, you might think that it would not contribute much to the shopping district. As young Rakugo story tellers started hanging out in the shopping district’s izakaya [Japanese-style pubs], and the local businessmen started to join them. They would get together and talk about stupid stuff and have a great time almost every night. Funny Rakugo story tellers and locals that were connected to the area eventually turned the ideas thrown out over drinks into realistic events for the locals. For example, people threw out whatever ideas they had for events such as, “A Field Trip of One-Day Apprenticeships” at the shopping district, granting a “Certificate of Walking from End to End of the Shopping District,” and “Street Performance Championship,” etc. You might say that these are silly ideas, but the district was crowded beyond what anyone could have imagined – ideas that people liked would turn into actual events within the next month, and these events created a gateway to draw in a large number of people. It was truly a “soft local production for local consumption.” Nowadays, it is surprising that there are more than 25,000 people walk through this shopping district every day, making it Japan’s busiest shopping district.

When you think of the Hanjou-tei as an example, the number of customers could be the basis for the evaluation of operating cultural facilities. However, if the role of cultural facilities is to give energy to the local community, then the number of visitors alone cannot be a reliable measure of their value and effectiveness. It can be said that having the Hanjou-tei there, the Rakugo story tellers, and local businessmen all getting together over drinks were all important cultural factors to the [the success of] Tenjinbashi-suji shopping district. And most importantly, the miracle of becoming the “Japan’s busiest shopping district” was achieved because of all the locals who love “Tenman Tenshin Hanjoutei.”

I felt that the story of the Rakugo story tellers and local businessmen is similar to Mr. Yoshiaki Nishimura’s example of “the style of not prioritizing the mission, but whoever happens to be there is everything” in our “5th Foundation Course: Research on How TOBIRAs Work.”

When operating things such as cultural facilities and cultural projects, whether or not you are loved by the locals and using creativity to make the locals love you is a very important point. The TOBI Gateway Project is the same way. In recent years, projects connecting the local community and art, such as the “Echigo-Tsumari Art Triennial” and “Setouchi International Art Festival,” are gaining more and more attention. It can be said that they have become a success through artists coming face-to-face on the soil with the local community’s unique nature and history and creating original art in the local community that moved the locals’ hearts. Also, these processes resulted in the achievement of a creative time and space where regional and global characteristics can coexist, and despite being held in a suburban city, the Setouchi International Art Festival recorded 940,000 visitors.

Using these art projects as examples, Mr. Hirata expressed the importance of Cultural Self-Determination Ability– such as “what are your own values?” and “what can we do to appeal to more people for regional developments in the future?” If we cannot cultivate our own Cultural Self-Determination Ability and instead rely on others to decide our own culture’s values, then the regional unique cultures will be swallowed up with big cities’ capitalistic tendencies, like a failure story of a Bubble Period’s city plans, and things will only go downhill.

—I believe that Mr. Hirata’s lecture could be a guiding philosophy for the TOBI Gate Project. Also, there were many parts that overlap with our own projects, which made me feel like we had received a great deal of support. Going forth, we would like to devote ourselves to see how much of the ideal we can turn into reality. (Tatsuya Ito, Manager, TOBI Gateway Project)

2012.07.01

6月3日に行われた基礎編に引き続き、平田オリザさんのワークショップ応用編が開催されました。今回はとびラー候補生(とびコー)さんに加え、学芸員の稲庭さん、佐々木さん、田村さんも一緒に参加されました。