2017.01.27

11月中旬 秋晴れで空がどこまでも高くつきぬける中、

僕は東京藝術大学 上野キャンパスにいました。

うっそうと生い茂った木々。

時々聞こえる何かを叩くような音。

そこは大学というより、初めて訪れる町のような感覚でした。

インタビューを依頼したのは、鈴木弦人さん。

東京藝術大学 大学院 彫刻科に在籍され

現在は卒業制作に打ち込んでいるとのことで

お話を伺いに来ました。

待ち合わせの場所に到着し、

鈴木さんらしき人を探します。

すると、10メートル先にある大きな工場のようなところから

背の高く、それでいてがっしりとした男性が出てきました。

もしかして!と思い 「鈴木さんですか?」と尋ねると

「はい。」との返事が。

黒いパーカーに、ところどころシミがついた黒いズボン。大きく丈夫そうで存在感のあるブーツ。首にかけた黒いタオル。目を凝らしてパーカーを見ると、左胸部分にミッキーマウスのデザイン。

それは、自分が想像していた、いわゆる「街中のアパレルで揃えたかのような学生の服装」というよりも

まるで職人が 自身の作業に打ち込む際に 無駄なく、作業に没頭できるように動くことのできるような佇まいでした。

鈴木さんが出てきた工場の入り口には広いスペースがあり、

そこに堂々と立っていた 見たこともない植物のような、金属製の2~3メートルあるオブジェこそが

鈴木さんが、大学院生活の最後の制作物として取り組んでいる作品でした。

とにかく、大きい。

まるでCG映画のワンシーンを一時停止したかのような光景。

全体は銀色で、枝のように伸びている部分に顔を近づけると、鏡のように反射して映るボディ。

「素材はアルミ金属を使って、制作物をつくっています。完成までもう少し大きくなるかな。一度に大きくはつくれないので、それぞれの部分を繋ぎ合わせて一つの大きな形にしていっていますね。

この独特な造形は“間欠泉”がイメージの元になっているとのこと。

土の下から湧き出てくる、熱くて激しいエネルギーが

上にむかって立ちのぼる様子を想像しながら制作しているそうです。

東京藝術大学 彫刻科に入学して、最初の2年間は木彫・石彫り・金属など様々な方面から彫刻を体験された鈴木さん。その中でも一番“金属が楽しい”と感じたそう。

「木材や石を使う彫刻制作は、一番最初に決めた通りに制作を進める必要があるんです。けれど金属は、進めていく途中で『あ、やっぱりここはこうしてみたいな』と思った部分に手を加えることができて、そこが面白いなって。」

素材に手を加える点では同じでも、木材や石を彫ることはいわばマイナスの作業。しかし金属は溶接を通してかたちを変えることもできるプラスの作業でもあるんですね。

「大きな材料がなくても、今ある小さな素材を繋ぎ合わせることができるんです。この作品も、近くに落ちているアルミの破片をくっつけて作っている点が何か所もあるんですよ。」

作品の傍に、鈴木さんの名前である“弦人”と大きく書かれた道具を発見。これは、なんですか?

「これですか、これはバッファーという道具ですね。」

23年間の人生で初めて出会う未知の道具。いったいどのような使い方をするのでしょう。

「素材のツヤを出す時に使います。布のようなものが付いた先端部分が回転して、触れた部分を高速で磨き上げる感じですね。ちょっと実際にやってみましょうか」

電源を入れると、さっきまで静かだったバッファーの先端部分が威勢よく動き出しました!

キューーンという音をあげて大回転!なかなかの迫力です。アルミの部分に当てると…??

お分かりいただけるでしょうか。写真中央のバッファーを当てた箇所が

まるで納車したての車の如くピカピカに輝いております。

ちなみに、そっとあてただけでかなりの効果でした。思わず自分も大興奮。

「最終的には、作品のすべての部分にバッファーを当てて、光沢を出せればなって考えてます。なので卒展に展示する頃には、今より見たときの印象もだいぶ変わるんじゃないですかね。」

バッファーの他にも、アルミ部分を叩いて表面の質感を変える(手作りの)金槌や、溶接作業の際に出る火花から守ってくれる革の手袋など

まさに「仕事道具」とも呼ぶにふさわしい 使い古されているのに何故か品性すらも感じさせる道具が多くありました。

「たまに、作品の傍で見に来てくれた方と話す機会があるんですけれど

作品について、自分の口から伝えたいことはあまり多くなくて。

でも、この金属を叩くのに使った金槌、こんなに重たいんですよって

道具の話は伝えたくなっちゃいますね。」

それにしても大きな造形物を製作されている鈴木さん。

“いったいいくら費用がかかるんだろう?”

素朴に思ったこの疑問にも、鈴木さんは優しく答えてくれました。

自身で材料を全て調達するので、素材の値段によって比例していくそう。

「ただ、作るだけじゃなくて、必要以上にお金をかけなくても制作はすることができるんだなって。他の仲間が作った作品よりも 費用を抑えて作ることができたら、個人的にはちょっと達成感を感じますね」

東京藝術大学に進学されたきっかけをお聞きすると

中学生の頃には既に”日本画”に興味を持っていたとのこと。

「当時好きだった漫画家さんが、美大の日本画科出身だったんです。それで興味を持って高校でも絵を描いたりしたんですけれど 絵を描いた後に絵の具が乾くのが待てなくって。『性格的にも向いてないのかも』とか思いつつ、デッサン等に取り組んでいました。」

浪人生活を経て、見事東京藝術大学に進学された後は、木彫や金属など様々な表現に触れ、

休みのときは取手キャンパスの草原を仲間とただひたすら走り回るなど

まさに柑橘色の学生生活を過ごした鈴木さんの原点は

尊敬するアーティストの方によるものでした。

1時間ほどお話を伺ってる最中も、常にどこかから色々な音や人の声が聞こえてきた東京藝術大学。夕焼け時間も相まって、思わず自分の大学祭前日の光景とシンクロしたかのような感覚になりました。

最後に、この作品は卒展で展示された後どうされるのかをお聞きしました。

「実は、今まで制作してきた作品はほぼ手元には残ってないんです。」

えっ!?なんとも意外な答え。制作し終わった作品はどうしてるんですか?

「もう大体壊しちゃってますね。飽き性なんですかね。目の前の作品を制作している最中でも、頭の中では次はもっと違うのつくろうかな~とか考えちゃってたりもして。ずっと形に残し続けることにこだわりはあまりないんです。」

成程。形に残すことよりも、作品と向き合っている瞬間が作り手として大切な時間なのかと、納得しました。

「でも、これはとっとこうかなと思います。これからはなるべく残していけたらな~って。最後だし、一応なんですけれど。」

自身が打ち込んできたことを、集大成として形にする体験を

人は生きているうちに何度行うことができるのでしょうか。

“卒業”という言葉を聞くと、少し感傷的に感じたりすることもありますが

鈴木さんの、少しクールに聞こえる言葉や、道具を手に取る姿を見ると

いつも通り、ただ、真っ直ぐ作品と向き合い

制作の日々を過ごされているように感じました。

秋晴れの透き通った空気の中

鈴木さんが丹精をこめてつくった彫刻は、

まるで天に向かって立ちのぼるかのように

その動きを携えて、今か今かと完成を待っています。

この滑らかなかたちが、余すことなく光りかがやくとき。

初春のころ、僕はまた新しい気持ちで

この作品と向き合うことになるのでしょうか。

執筆:三木星悟(アート・コミュニケータ「とびラー」)

2017.01.18

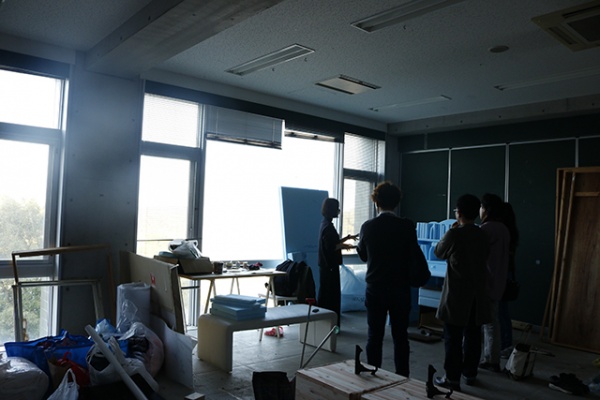

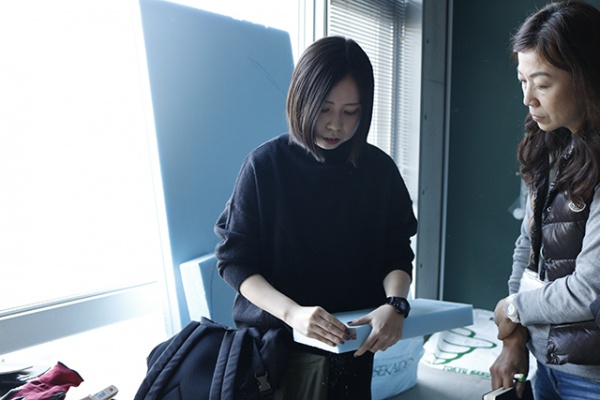

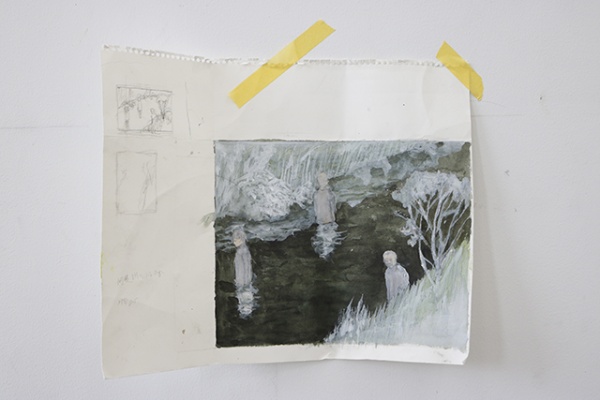

上野から常磐線に揺られること45分。茨城県取手市にある芸大取手キャンパスへ、卒業制作に励む芸大生、黒松理穂さんに会いに行ってきました。

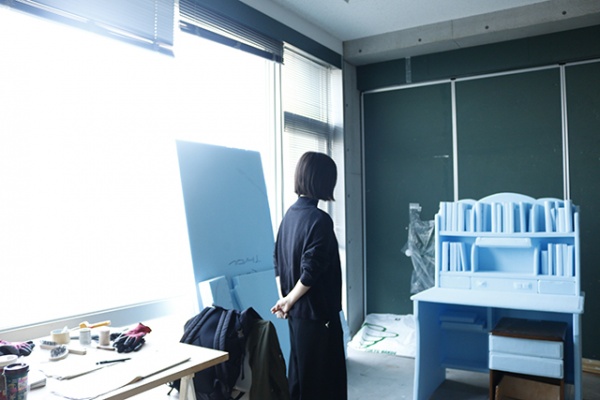

広い部屋に雑然と置かれた資材、工具等などの中に、澄んだ水色のスタイロフォームで制作された作品がすっくと“凛々しく”立っていました。そこにはスポットライトのように窓から光が差し込み、作品の凛々しさを一層際立たせていました。

週に5日、ここで作業をしているという黒松さんに、卒展の作品と制作に至る経緯など、子供の頃の記憶にまで遡ってお話をお伺いしました。

■卒展出品作品について

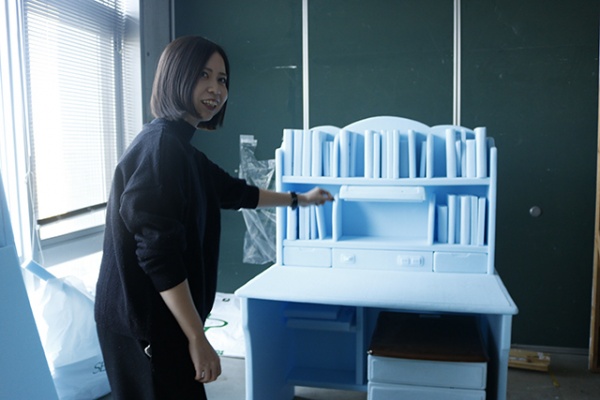

初めて目にした“水色”のスタイロフォーム(発泡スチロール)。これを使って黒松さんが制作していたのは、懐かしの(笑)「学習机」でした!

この「学習机」を作るに至った経緯

—————「拾ったもの(断片)から元の形を想像して復元する」という、これまでの制作の「最終形」が今回の作品です。子供(小学校高学年)の頃、生活環境が大きく変わる出来事がありました。家具の大半を最初の家に残して、引っ越しを繰り返すことになりました。今の実家には子供の頃に使っていたものはほとんどありません。

そんな中、子供の頃に使っていた学習机のキャスターが、当時近くに住んでいた方の家に残っていることが分かり、引き取ってきたんです。そのキャスターから記憶をたどり、当時使っていた学習机をほぼ原寸大で復元していきます。—————

黒松さんのテーマは、過去の記憶をたどり、自分を見つめ直す、「私の記憶の再生」でした。

—————この作品は、「もう元に戻れない、取り戻せない過去」、「子供の頃の幸せな記憶」を表現しています。家には、当時のホームビデオも残っていました。その中から、特別な行事やイベントを撮影したものではなく、家族の「日常」を撮影したものを選んで、音声だけを作品の中にスピーカーを取り付けて流すことを考えています。映像まで出してしまうと「自分語り」のようになってしまうので。————

黒松さんが今回の作品で表現するのは、“華やかで明るい”とは対極にある、日常を切り取った、どこか“懐かしさ”を感じる“過去の記憶”です。

机の本棚には、スタイロフォームで一つ一つ作った「本」がありました。これらも黒松さんの「記憶」から再現されたものです。その書名のいくつかも黒松さんは覚えているそうで、「自由自在」や「特進クラスの算数」という参考書(笑)、お母様から譲り受けて大好きだった「シートン動物記」が再現される予定です。

この作品のキーワードは、「日常の記憶」。

—————当時当たり前だと思っていた日常が、突然奪われたことでその幸せに気づきました。なくなってから気づくこと。この作品ではそのことを表現したいと思います。—————

水色のスタイロフォームを材料に選んだ理由は?

—————まだ粘土とスタイロフォームとどちらにしようか悩んではいるのですが、スタイロフォームは、記憶を忠実に再現しやすかったことと、「軽い」素材を使うことで、「現実味がない、儚い、脆い」と言ったことを表現できるのではないかと思いました。

色は思い出せるところだけ彩色する予定です。思い出せないところはそのまま、スタイロフォームの水色を残します。—————

黒松さんは、私たちよりもずっとずっと豊かな感受性をもっていて、幼少期に起こった出来事が彼女に与えた衝撃は周りが思っている以上に深く、そしてその記憶はとても「鮮明」なものでした。

7月中旬に行われたWIP(ワークインプログレス)での担当教授からの言葉についてもお話ししてくださいました。

—————「拾ったゴミ(断片)から想像して原形を復元する」という作品について、「生産と消費について表現したいのか?」と言われました。それは私が言いたい事とは違うなと思いました。私が表現したいのはそうではない、と。だから、これまでやってきたことをもう少し発展させたいなと思いました。—————

この時から、黒松さんの制作は、「断片から想像して原形を復元する」という、ある意味周囲に受け入れられやすい作品から、「記憶を頼りに原形を復元する」という方向にシフトチェンジされていきます。

—————これまで、自分のことを作品にすることが苦手で、拾ったもので見た人が、「分かりやすい・共感しやすい」作品ばかりを作ってきました。卒展にこの作品(学習机)を出品することで、これまで周囲の人に話してこなかった自分自身の生い立ちや過去をさらけ出すことにもなります。(決断するまでに)迷いはありましたし、葛藤もありました。でも、勝負するなら今かなと思いました。子供の頃のこの経験が、今、作品を制作するモチベーションになっていると思うので。—————

黒松さんの中でこうした「葛藤」があり、その中でこの卒展の場を勝負の場と「決意」し挑んだ作品です。制作過程では、過去に記憶を遡り、自分自身を見つめ直す機会が何度となく訪れていることと思います。 最初に感じた作品の“凛々しさ”は、この黒松さんの「決意」の表れだったのだと納得しました。

—————自分の過去を作品にすることにまだ迷いはあります。でも、一人でもこの作品に共感してくれる人がいたら嬉しいです。————

黒松さんがこの作品を完成させた時は、幼少時から続く記憶の一つの完成形(ゴール)となると共に、新たな、そして大きな一歩となることと思います。

今日も、広い部屋でスタイロフォームをカットし、ヤスリで一つ一つ丁寧に削りながら、自分と向き合っている姿が思い浮かびます。

執筆:河村由理(アート・コミュニケータ「とびラー」

2017.01.18

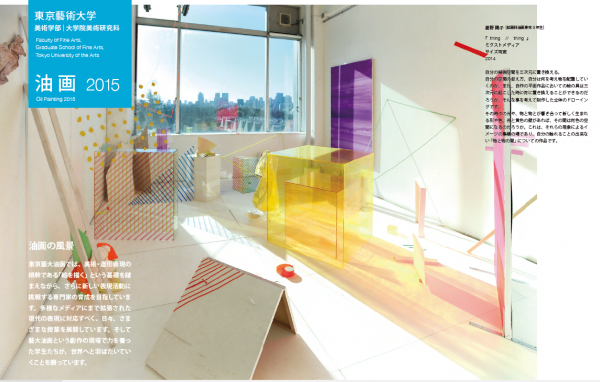

星野さんのアトリエは東京藝術大学絵画棟の7階。窓から眼下に広がる上野の杜は、その日はまだ11月だというのに朝から降り続く白い雪と樹々の紅葉とのコントラストが一枚の絵のようでした。

アトリエは白い空間で同じ油画専攻の楊博さんとシェア。そこには次の構想を練るためのポップで色とりどりな“モノ”たちが置かれていて、中には消臭ゼリーやウィッグなど、一見絵画とはかけ離れているように思えるモノも。触ったり、置いてみたりしながら、モノの様子を探っているのだそう。

インタビューは星野さんの小気味良い語り口で進んで行きました。

ボールの中にはゼリー状のものが入っており、そこに仕掛けたライトが不思議な光の拡散を見せています

◆星野さんの作品は、平面的な絵画とは異なる三次元での立体表現。こうした作品へ至った経緯をお聞きしました。

4 年生のとき、小林正人先生の授業『現代美術コース』で、たったの5 時間で作品をつくるという課題がありました。使う材料は、他の受講者たちが星野さんのために 100 円ショップで買い集めた 200 点のモノ。この経験が作品づくりの大きな変化になったといいます。

「とにかく設計図も計画も立てられない中で作らなくてはならなくて。作品の概念がよく解らなくて、感性も何かわからないし。でも、とにかく『終わる』ってとこを見せる。このことが作品作りの転機になりました。」

フラフープにボール、中央に掛かっているものはホログラムシート!

北側に面した天井高のある空間にいろんなものが置かれています

「もともとは平面作品を描いていましたが、モノを自分で重ねて、そのモノが連続して重なるものをモチーフとしていて。わかりづらいと思うんですけど、自分でその物どうしの関係を操作していくことに興味があって。」

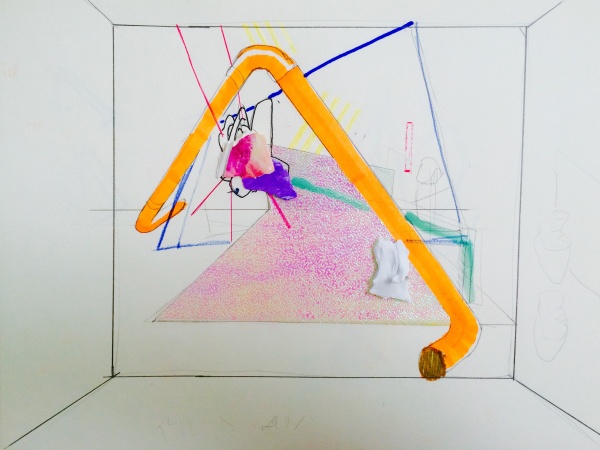

平面作品

「1 年生の時の『東京マケット』という課題は【東京を歩いて感じたことを作品にしなさい】というものでした。自分が考えたのは『赤いビルと黄色いビルがあったらその間はオレンジの空間になるのではないか』とか、例えば『ビルがたくさんある中でひとつがあたたかくなったら周りも変わっていくんじゃないか』とか、そんな当たり前のことなんですけど。そんな単純な発想を模型にした時に、なんだかすごく自分の中で楽しい実感がありました。そこで起こっている現象が楽しくて、それも大きい部屋でやってみたいと思うようになって。」

『Things//Things』

「大きな部屋では、1 日の太陽光の移り変わりを利用して、自分が意図したものと、その時に現れる新しい形や色とで、新しい関係をつくることを実験的にやってみた。自分のイメージしたものが 3 次元に置き換わった時に『その空間に足を踏み入れる感覚』が絵画よりもとても強く感じられたので、そこからいろいろやってみたいなと思うようになりました。」

絵画棟での展示の説明

「その後に絵画棟 1 階のギャラリーを利用して、自分で何となく描いていたドローイングを三次元にしてみました。正面から見るとただのペインティング作品ですが、横からも上からも見ることができる。つまり最初の視点は絵(平面)なんですけど、その中に自分が入っていけるような空間を作ることをテーマに、しばらく制作しました。」

「去年、3 年生の時の作品をアーツ千代田 3331 のギャラリーに展示しました。入り口から最初に入っていくときは、正面からだと二次元的に見えるようになっているんだけど、そこから中に入っていくことができるというもの。とにかく絵の中に入ってみたいという単純な動機でやってみました。

ここまでの作品は自分のテーマがあって、ドローイングのラインはモノで置き換えると何になるんだろう?と。最初は置くモノを自分で作っていました。なのでちょっと『固い』といわれて。」

「それが原因で、4年生の『現代美術コース』での課題では全部 100円ショップの小さな物を使って、設計図のない状態でいきなり作ることを要求されました。置かれている物どうしの関係性とか、そこでしか生まれないおもしろさに、感覚として気づくことができた。」

「たとえば、ちょっとこれは洗濯ハンガーみたいなものなんですけど、」

同じ講座の方たちが星野さんのために無作為に集めた 100 円ショップのものの一部。ボールの中 はぷにょぷにょした昆虫ゼリーに消臭ビーズ、底には光るライト!星野さんの発想の一部を再現。

―ハンガー?

「そうなんですけど、それがそう見えなくなる瞬間が面白い。『どうしたら作品になるんだろう?』『作品って何だろう?』『人が見て、かっこいいってなったらいいなぁ』とか考えながら、そういうところを探していろいろ遊ぶ…その時遊ぶ余裕は、まったくなかったんですけど。」

「最初は平面で描いたものを 3次元にしていたけれど、それは何も描かない状態から作っていった、初めての体験でした。」

「でも、まだうまく消化できないままで。そんななか、2016 年の夏に石橋財団国際交流油画奨学生として 2 か月間アメリカのいろんな州に行かせていただきました。そのことを報告展示する課題が先週あって、作品を作りました。こんな感じです。」

2016 夏の報告展示作品。正面には映像が投影され、両側はミラーフィルムに移り込んだ映像やモノたちがまた違った姿を見せています。床にも仕掛けが!

「正面には向こうで撮ってきた山や川などの映像を映してます。」

―自然の映像ですね?

「そうですね、それを映して。両側の壁にはミラーフィルムを張ってあるので、正面の映像がミラーフィルムに反射して、色や形が強く変わる演出をしました。」

ミラーシートに移り込む物の形があいまいになっている様子

アメリカの星野さん好みのテンションのものたち

―正面の映像だけでなく、ライトなどいろんな光るものが置いてあります。

「他にも、ラスベガスで拾ってきたエッチなカードとか、黒人向けの化粧道具で、ビビッドでどぎつい紫色とか…そんなテンションがすごく好き。それを並べて置いてみたり、組み合わせてみたりして『かっこいい』『おもしろい』と感じたところを探しだし、空間を仕上げていきました。」

―おもしろい。

「ふふふ(笑)。『何か強い色があったら、その隣に負けないくらい強い色を立ててみよう!』みたいな空気がアメリカにはあって。そんな、自分にとって面白いなって思うことを伝えたくて、映像をフォーカスして撮ってみたり。また監視カメラも作品空間のなかに 1箇所あって、自分が動くと同時に、床にもその映像が投影される仕組みになっています。」

―そこに入ると部屋全体が動いているような感覚でしょうし、両サイドのミラーフィルムに映り込んでいるものは、ゆがんでしまって原型をとどめていない様子ですね。

「そうなんです、なのでちょっと自分の感覚が破壊されていくような感じになって。何が本当で何が嘘かちょっとわかんないような。

元の形が何だったのかわからなくなる状態っていうのが、自分の一番の表現。最初に部屋に入ったときに、両壁に映像が投影されているなってことよりも、「あれ?なんか動いてる!」っていう不思議さとか、奇妙さとか、モノがモノでなくなる瞬間が一番気持ちいいかなって。

今はそこを目指して、そのプロセスをより深く体験できるものを探して、いろいろモノを探って考えている状態なんです。」

―『現代美術コース』の課題では、それまで 2 次元のドローイングから 3 次元に起こしていたものから、ダイレクトに 3 次元で表していく方法へと、いわば制作過程が真逆になりましたね。

「その方が理由がいらないし、自分の欲求に対してどこまでも感覚的になれるというか。最初にドローイングを描いて、それを立体に起こすってなると当たり前のことなんですけど、最初の計画に自分が縛られてしまい、そこで新しい出会いがない。なんか出来上がった後に自分で予定どおりに作ったけど、それで?っていう状態がすごくあって。」

「それに光などは絵の中では作れなくって。動きとか、光が当たってできる影なんかは、絵で描くと逆にうそくさくなってしまう。けど、自分が三次元で入っていって体感できると初めて美しく思える。そこに意識が向いたのは小林正人教授の課題があったから。そこからは考えない方法を考えている感じ。」

◆卒展に向けて

「今は次の展示に向けてモノを違う状態にできて、人に見せる・見てもらいたいっていうのを考えて探っている状態。かっこいい状態を考えながら、触って、様子見て、っていう感じです。」

―作品を現場で作り上げる星野さんにとっては、時間も重要なポイントになります。

「東京都美術館での展示時間が五時間と限られているので、その時しかできないものにどれだけ取り組めるかっていうのが課題。何を削って何を残すかについて、その場所での制約を含めて、どれだけ自分のパフォーマンスができるか。材料を集めつつ、かっこいいものの組み合わせを探しています。特に東京都美術館の中では暗室が作れない。明るい中で映像をどう映すか、どう伝えるか。そこは初めに計画しないといけないので、今はやることを整理しています。」

自分の作った映像等を今度は絵にして、どんな空間だったかなど思い出しながら思考を整理

◆星野さんご自身のこと

―小中高生はどんな学生でしたか?

「小さいころは絵を描けばほめられるのが嬉しくて描いていました。私って才能があるんだと。でも絵画コンクールには一度も引っかかったことはなかったけど(笑)。

中学時代、地元は結構ヤンキーばかりで(笑)そういう雰囲気の学生時代。卒業の時に何か自分だけのものがほしいと思って。

高校の合格発表の日にもらった予備校のパンフレットを見て『藝大ってかっこいいじゃん』と。ほんとにそれだけ。『私は周りとは違う何かがあるはず!』と。きっかけは人に認められたい、一番になりたい、自分だけの何かが欲しい、って思ったこと。」

―気持ちいいくらいきっぱり。

「やー、ウソついても仕方がないなっていう。教授には最初、アート論を勉強しなさいと言われましたが、でも本を読んでも要約はわかるんだけど、その先に進めない本がたくさんある。どうも作品作りにおいてコンセプチュアルな表現がしっくりこない。教授に相談すると、もういいからそのまま行けと。自分が作品を作るための社会的な意味やコンセプトを考えすぎずに今の勢いで突っ走れと。」

「世の中に対して、より自分の刺激を求めている。」

―熱いですね。

「ネガティブかもしれないけど、自分のコンプレックスがあるから作品で認められたい、見て欲しい。美術より他に好きなことがたくさんあるし、そっちも全然楽しい。でも講評近くなったらやらなくちゃ!となって、やればすぐ作品作りがスタートできる。」

―そのスイッチがあります?

「もっと早くやればいいのですが。時間がないとちょっとでもよい方の選択を、パッとするしかない。そんな風に作った方が評価がいいんです。永遠に時間があると思い込んでいる自分は優柔不断。切羽詰まったら、より感覚的になれるし失敗しても堂々とやるしかない。一瞬一瞬の方が楽しい。やるしかない。」

―いさぎよさもありますね。

「迷ってるとかっこ悪いから、間違っていても 100 パーセント正しいって顔をしようと。勢いやパワーもあるし楽しい。教授には、その楽しいことから言いたいことのコンセプトを言葉にできるように、もっと自分らしさの整理をするように言われています。」

「とにかく手を動かして、自分がよいと思ったものを出会わせて。そこから出てくるものしか信じられないかな。」

雪の寒い日だったことを忘れるくらいの熱く面白い本音トークで進んだインタビューでした。見る人を楽しませたいという作品たちが示すように、人を惹きつける魅力もある星野さん。一つ一つの課題やイベントを経験するごとに、どんどん新たな感性が生まれていくような星野さんの視点。卒展ではどんな作品が作り出されるのでしょうか。

またアートプロジェクトにも興味があり、企画しながらいろんな人の体験も広げていきたいという野心も語ってくれました。彼女の今後の活動も、どう展開していくの目が離せません。

東京都美術館での卒展、その直前に行われる藝大での展示にも是非足を運んで体感してみてくださいね。

執筆:大川よしえ(アート・コミュニケータ「とびラー」)

2017.01.14

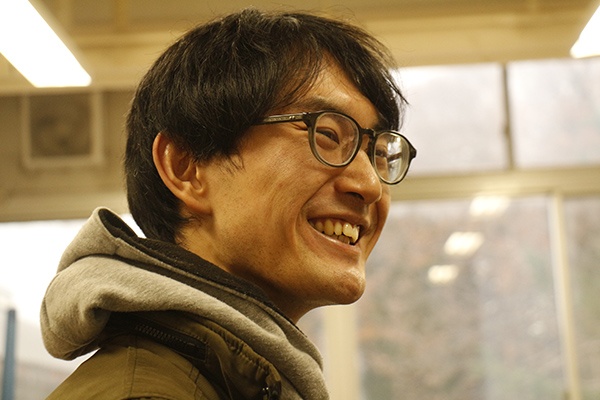

11月末の晴れた日の午後、絵画棟の1Fで楊さんと待ち合わせ。エレベーターの扉が開いて出てきたのは長身でスラッとした優しそうな青年でした。黒の革ジャンに黒のパンツ、長髪を後ろで束ねたスタイルはミュージシャンのようでもあります。「お待たせしました」と静かに言葉をかけてくれて7Fのアトリエへ案内してくれました。アトリエへ入って行って、最初に目に付いたのは壁に掛かった大きな布です。どうやら、これが卒展に出す作品になるようです。物静かでソフトな感じの中にもどこか強い芯を秘めているようなこの青年が作る作品とは、一体どんなものなのでしょうか。

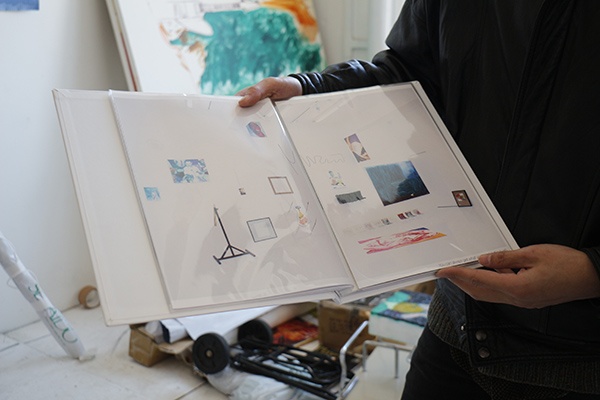

まずはポートフォリオを見せてもらい、今までに制作した作品の説明をしてくれました。

◆これは、旧豊島区の区役所が解体する前に「さよならパーティ」を行うことになって、19人の同世代の人々と一緒に展示をしようということになり、壁に文字を彫った作品を作ったんです。

◇アートギャラリーではなく、市役所で?

◆はい、そういう機会でした。これは「You are Wonderful」 という文字の「You are」をもう一回繰り返して上に掘ったんです。元ネタはデビッド・ボウイの歌詞なんです。1月に亡くなられたので、2月の展示で作成しました。現場の手伝いのようなアルバイトをしていた時にこのビルが解体されることを聞いて、業者の方々が建物に入る時にこれを見られたらいいなと思って掘って残しました。いい機会でした。

◆これは、3年生の時に学年全体の総まとめの展示を3331でやったんですが、その時の作品の写真です。こういう作品をアトリエで作ってるんですが、これに相当する今年の作品がこちらに貼ってあります。これはボール紙を潰して実験的に作り、今年の芸祭に出しました。手を動かすのが好きで、こう言う素材を見つけては何かやってみようという試みを続けています。こういう作品についての説明を何かと求められるんですけど…、まあ、苦手だなあ、と。それはこれからの課題かなと思ってはいるんです。

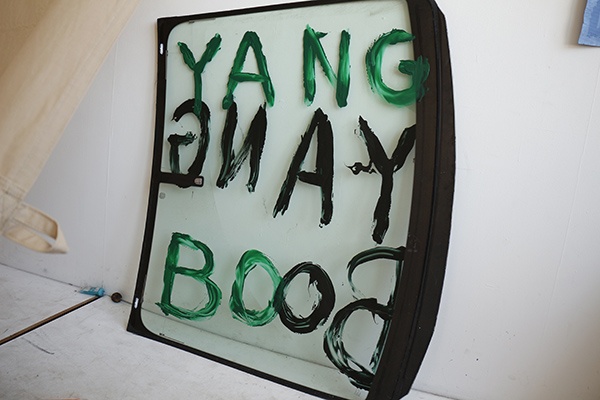

◆次にこの作品。僕、中国人なんです。芸大には留学生としているんですが、日本には小学生の頃からずっと住んでいます。中国語の名前をヤン・ボー(YANG BOO/楊博)といいます。これマイクロバスのガラスだと思うんですが、友達が拾ってきたものです。そいつがなんか作ろうとしたらしいんですけど思いつかなかったので「あげる」と。それをもらって、じゃあ僕のものになったから僕の名前を書くわって言って、ヤンボーって描いて、ガラスは透けているし表と裏があるから裏にも描いて。あれは手で描いたんです。その、自分の名前を自分の手で描きました。

◇なぜ手で描いたのですか?

◆この作品は、先程の文字を壁に彫った作品の後に作ったものなんですね。壁にも筆で描くことができたのですが、でも彫ったことで強烈な印象の作品になりました。見てくれた方々からも「彫ったことと文字の意味が別々にあって、彫ったことの方がむしろ先に見えてきて、それが作品になっている」という感想をいただきました。引用している言葉の文字(しかもデビット・ボウイの歌詞という強いもの)を彫ったことによって自分の作品になったということです。それと同じように、ガラスに手で描くことで意味が出てくる。文字にはその意味があって歴史があると思うんですけれど、モチーフを選んでそれを打ち出していくっていうよりは、それを打ち消していくみたいな感じです。

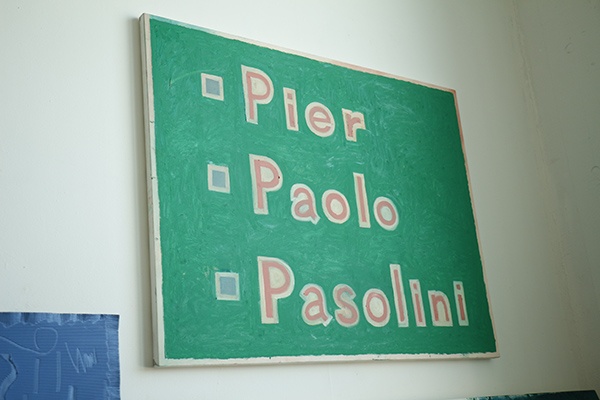

◆これはピエールパオロパゾリーニ・・・というイタリアの映画監督の名前なんです。イニシャルがPPPで、アンケートみたいだなって思って「お好きなPはどれですか」というようなイメージです。意味とか背景が記号みたいなものとして言葉があったとしたら、その成り立ちを無視してその言葉だけで存在した時の「どこにもいかない感じ」「それでしかない感じ」というのが、結構いいなと思ってます。

「それでしかない感じ」は、存在しているだけになるんですけども、でも存在しているだけっていうことを許されないわけにはいかない。ある言葉や、人でもいいんですけど、その意味とか背景等には良いものもあれば悪いものもあるじゃないですか。例えば、悪い方の背景を持っちゃったものが、じゃあ、存在しちゃいけないのかって話をした時に、その存在をすごく許容したい。どんな存在も応援していきたいんです。

作品作ってメッセージは何かと聞かれた時に一つ人に言えることがあるとしたら「いろいろあるけど、頑張って生きていこう」ってことかな。

だけど、なんでもいいという訳にはいかないと思っています。自分の制作の部分でどういった質を出せるかですね。

例えば「知らないものは存在しないのか」みたいな話をした時に、でも絶対に存在している。知らないだけで、知らなくても存在している。という存在。でも、それを、逆側からいうと否定してほしくないという、それは自分の感情に近いのかもしれない。正を掲げるというより、負を掲げる。例えば、自己紹介するときに「わたしの名前は何」というのでなくて、わたしの名前は「こうでもない、こうでもない、こうでもない」というのを60億回以上続けるというようなものです。

美大生が絵を描き始めるきっかけみたいなのって、気づいたらなんかやってたという人と、憧れでやった人がいると思うんですけど、僕は圧倒的に憧れでやってて、憧れでしかやってないかもしれません。その対象は自分の好きなもの、それこそデビッド・ボウイだったり。例えば、自分が誰かに憧れているという構図を俯瞰した時に、自分の名前を描いて自分を登場させることで、なんかこう自分をちょっとバカにする。「あ、あいつ、デビッド・ボウイ死んだからってボウイの歌詞使って作品作ってんぞ」ていうのを、自分で俯瞰してその構図をバカにするんです。憧れという感情は、愛の一種だと思ってます。自分が誰かに憧れている時に、自分とは違うから「この人に絶対なれない」っていう絶望の気持ちが同時にあると思うんです。その二つを合わせたものが作品に出せたらいいなと思います。その両方がないと、さっき言ったように存在ってものにならないと思っています。

そして、作品は出来上がったら自分から離れていくと思っています。単純に作品の方が長生きの可能性が高いじゃないですか。「作品は自分の子供だ」みたいなことをいう人がいるんですけど、僕もそう思っています。成人するまでが制作期間で、完成したらそいつはそいつでやっていくしかないんです。独り立ちですね。だから僕はそいつにやっていけるだけの教育って言っちゃ変ですけども、その、愛を注ごうと思っています。そいつは、僕が死んでしまったら説明ができなくなるので、その作品の一つ一つの存在をできるだけ強固な、質の高いものにしたいなと思っています。憧れとかそういった感情は、自分が美術をやるきっかけに密に接しているので、これからの作品の全体のテーマとしてずっとあるものだと思っています。

◇卒展ではどんな作品を作るのですか?

◆デビッド・ボウイの話の続きなんですけど、友達からの電話で「なんかボウイ、死んだ」って聞いて「まじか」ってびっくりしたんです。その後彼の音楽をしばらく聞き直している時に、さっきの作品が出てきたんです。すごく簡単に言えば「俺の作品をボウイには二度と見せられないんだ」って思いました、一度も見せたことはないですけどね。それで、亡くなった人のために作品作るよりも、生きてる人に向けて作品を作りたいなと思ったんです。それで今回の作品は、イギーポップという人がモチーフになっているんです。イギーポップに手紙を書こうと思ったんです。

◇手紙で何を伝えるのでしょう?

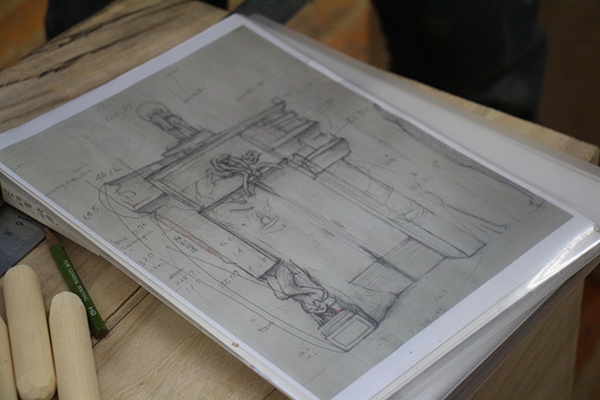

◆伝える内容は考えている最中です。イギーポップに何かを届けるためのものを作ろうと、計画をし始めたのがこれですね。木枠が入ったら、見え方が違うと思います。枠をつけて、ここをワイヤーで引っ張ります。

◇空間が広いから。ここで描くんですね?

◆はい、ここで描きます。

おっきい作品を作る…(少し考えて)なんだろう。一つめちゃくちゃ好きな作品があって、ジョシュ・スミスという画家のティラノサウルスの絵なんです。ティラノサウルスって全長が13〜15mくらいあるんです。それを、多分等身大で描きたかったんだろうな。等身大が描きたかったというだけで、10m四方のキャンバスを作ってそれに描いたんですよ、それがなんかすごくいいなと思ってます。

客観的に自分がどういう戦略をしているかは、まだはっきりしてるわけではないのですが、「一見、すごいバカ」を大事にしたいんです。「バカな自分を、死ぬほど隠そうとするんだけども、逆にバカ」っていうような作品が、すごくいいなーと思ってるんです。(笑)

楊さんは自分の心に添うような言葉を一つ一つ丁寧に選びながら、作品に込める思いを伝えようと一生懸命に話しをしてくれます。モチーフを通して作品に込める想いにはあらゆるものの「存在」を大切にしたいという楊さんの優しい気持ちを感じました。インタビューは楽しい雰囲気のなか、楊さんの話に引き込まれながら進み、次に美術の世界に入ったきっかけを聞いてみました。

◇美術の世界に入ったきっかけはなんですか?

◆きっかけは「憧れ」が始まりですね。

具体的に誰か、という訳ではなくて「絵描きかっこいい!」と、そんなもんだったと思います。

◇お話を聞いてると、「絵描き」や「ミュージシャン」の存在からも強い影響を受けていらっしゃるように思えるのですが、そういったアーティスト以外で楊さんが刺激をもらったり、憧れを持つ存在っていますか?

◆アーティストに限定しているつもりはないのですが、映画見るの好きだから映画監督をよく知っているぐらいですね。あと、友達がすごいです。何か成し遂げたというのではないのですが、フツーに遊んでいて、「あ、こいつ今いいこと言ったな」とか「あ、こいつ誰よりもバカだな」とか良し悪しはさておき、何か強いところを見せられると「おお〜!」っと思います。それこそ搬入の仕事をしている時に、職人さんが一瞬にしてステージを立てたり壁紙をビーっと貼ったりするのを見て凄いなと思いました。極論ですけど、みんな凄いですよ。生きているだけで凄いなと思ったりします。

◇油画科に入ったきっかけは何ですか?

◆ちっちゃい時に絵画教室に通わされていて、こう、ちょっとだけ得意だったとういうことです。

高校が宮城のちょっとした進学校で、みんなと同じことしたくないなっていうそのくらいの感情だったと思います。なんか「自分は違うぞ」みたいな中二病じゃないんですけど、システム化された受験勉強がちょっと嫌だなとは思ったことがありました。イベント等で絵を描いたら、「オー!」とか賞賛されて、ま、ちょっと得意になってたこともあって、ですね。

◇その段階で普通の大学へ行くより美大・芸大へ行きたいと思われたんですか?

◆普通の大学へ行って何するの?っていうのが思いつかなかった。いや、今でこそわかるんですけど、その当時は「美術」の方がわかりやすかったんです。

◇受験なさったんですよね?

現役の時はデザイン科を受けました。絵が得意で将来はそれでやっていけそうと思ったので、デザイン科で受けたんですけど、試験で大失敗しました。その後それまでの姿勢をすごく反省したんです。「あいつらと違うことをやる」って言いながら、みんなが進学のための勉強をしている時に美術室の裏に転がっていていいのかって。以前「俺は美術やってるから他の人達にとやかく言われることはない」と自分の中でいろいろな言い訳を作っていたんですね。結果としてなんだかんだ堕落していて、それで大失敗した。とにかく言い訳のきっかけを消そうと思ったんです。デザインって課題が固くて守んなきゃいけないルールが多くて、うまくいかなかった時にこれはこんなルールがつまんないからだとか、そういうことをたぶん思ってたんですよね。それで、油絵科だったら良くも悪くも全部自分次第だから。人のせいにできないような状況におきたかったという感じはあります。受かったタイミングが、その直前で「ちょっとわかったところ」でした。そうすると絵も明るく変わってきて良くなったと言われ、その勢いで、すっと入れました。

◇浪人の期間は絵を練習したというよりも、自分の考え方を整理して、心が整ったら結果もついて来たということですか?

◆そうですね。

◇油画は1〜3年の授業で描いてきていますよね?

◆油画っていうのは絵の具の種類のことじゃないですか、これは何かというと僕は絵画と言うんですけど、表現したいこと自体はそんなに変わってはないと思っています。

◇油画と言っても材料に固定するのではなくて、絵画という考え方ですか?

そうですね、油絵、まあ、でも今もう何でもやっちゃうじゃないですか。油画科。入ってからしばらくして思うのは、最終的に作品になった時の良し悪しとかっていうのは何を使って制作したかというのは全然関係ないと思うんです。素材は、慣れて扱えなきゃいけないということが前提なんですけど。

◇今年で大学を卒業されるんですよね。

◆そうですね。一応大学院受けようとしています。将来的には、もっといろいろなところへ行きたいと考えています。一つの場所に固執するような感じではなく、その時に何に出会うかということでしょうか。

来年2年間、この科に入れたらここを拠点として自分でいっぱい動いていきたいです。

◇将来目指すことは?

◆制作が出来る状況をとにかく保ち続けていきたいと思っています。コラボレーションの機会はちょいちょいあるんです。パフォーマンスをやってる人の作品の中で、ライブペインティング役をやるとか、ライブハウスでも展示したことが一回ありました。友達は「一緒にやってみよう系」で、すごく楽しいです。

◇話は変わりますが、楊さんって、バンドや音楽をやったりしますか?

◆やってないです。やってそうってすごく聞かれるんですけど、、いっぱい聞かれるから意識して「やってそう感」出してるんです(笑)。憧れるならやっちゃえよ、っていう話だと思うんですけど。やらない原因としては、やり始めたら今の気持ちが変わることがちょっと怖い気がすることと、単純にきっかけがなかったということもあります。まあ、なんかそのうちやる気はします。やらなきゃという気になる時が、出てくるかもしれないですね。

◇大学4年間、簡単に振り返ってどんな4年間でしたか?

◆そうですね、全部の期間がそうなんですけど、環境が変わって新しい経験ができて良かったと思います。そして藝大だから作品に集中してできたっていう、それだけでもけっこう大事だったなって思ってます。それから、将来のことも考えたし、いろいろなバイトをしたことにより、人にどう接したらいいのかっていう簡単で常識的なことがすごく勉強になりました。

◇どんなバイトをしていたんですか?

◆浪人の時は最初はコンビニから初めて、CDショップ、喫茶店、その後派遣の搬入系のバイトをやりました。今は予備校で講師もやっています。

まあ、普通に生きていくにあたって「自分だけじゃあどうにもならない」っていうことをすごく思いました。これだけはいいなと思うのは、憧れて始めてるから、フツーに好きなんですよ。だから、勉強も勉強という感じはしなくて、好きな人の画集をめっちゃ見るとか、それだけで楽しかったり、楽しいと同時に勉強になったり、それがいいかなーと思ったりしてます。

◇好きなことを続けて、それが仕事にもなるといいですね。

◆なったら、結構いいですね。目指したいですね。

◇宮城県から上野に来てどう感じました?

◆最初、立川だったんですよ。宮城から立川へ行きました。最初は生活のいろいろ、お金の支払いとかそういうところで面倒くさかったです。慣れてくれば、けっこう適応力がある方だと思っているので大丈夫なんですが。地元の食べ物が時々恋しくなります。そのくらいかな。たまに帰省すると嬉しいですね。

これほんと、絶対嘘って言われるんですけど、餃子が一番好きなんです。水餃子。

今年9月に一回中国へ帰ったんですけど、おばあちゃんの作る餃子がすごい美味かったです。

向こうで餃子は、家族が集まった時にみんなで作ります。小麦粉から練って皮から作るのでその日はほんと1日餃子の日っていう感じです。だから、向こうでもちょっと当別な感じはありますね。家族団らんの場っていう感じです。

高校時代から大学時代、自分の気持ちをきちんと掴んで内省しながら誠実に着々と人生を歩んでいるなあと感じます。『「中国人だから餃子好き」っていうとみんなが”嘘”っていうんですよ!』と明るく笑う楊さんの友人もきっと素敵な人たちでしょう。暖かな日差しの中で、楊さんの優しい気質が垣間見えるお話を伺っていると、心もポカポカと暖かくなっていき自然と笑みがこぼれます。

次にアトリエについて伺ってみました。

◇こちらは何人の方で作業してるんですか?

◆ここは、3人で使っています。

いや、ほんとに、「もう、お前ら、とにかくそこから、出てくるな」って言われてます。

◇3人同時で作業をしますか?それとも入れ替わり?

◆計画はしたことないですけど、そこはお互いの感情を見て作業する感じです。でも、作るっていうより物が多いっていうのが特徴ですね。こいつ(隣のスペースの学生)は夏前にこの布くらいでっかい棚を作って、それが真ん中にドンってあって「ど、ど、どうしてくれんの?」みたいな感じでした。今はバラして、なんか別のものを作ってますね。

アトリエはコースに分かれているんですが、うちのコースに、ちょっと物が多い人がいるんですね。向こうのアトリエとか行くと、カヤバ珈琲(藝大近くのカフェ)みたいに洗練された空間があって、座布団で珈琲飲むそんな感じだったりするのに、その隣にこの部屋があって、その、ちょっと申し訳ないです(笑)。

◇週5くらいでここにいらっしゃる?

◆今は週4くらいですね。ま、バイトの都合次第です。

◇文化祭の前日みたいですね。

◆まあ、なんかここの人たちは自分が散らかすって知っているから、人にも言えないのでお互いの空気を見ています。自分が多分、カヤバ珈琲のところとかに行ったら耐えられないかもしれません。ダメなところが似ると仲良くなるって、そう思います。

◇人に対して優しいですね、皆さん。

◆あ、なんか嬉しいですね。

どんな話を聞いても心優しいなと感じる楊さん、アトリエの仲間もなぜか同じようなメンバーが集まったようです。お互いの空気を読みながら、作りたい作品へ情熱を傾けている3人の仲間の様子が目に浮かぶよう。散らかった部屋というのは、彼らの頭の中に詰まっているたくさんのアイデアと同じ状態なのでしょう。部屋に散る様々な物たちは彼らにとって表現するために必要で大切な宝物に違いないのだと思えてきました。

◇最後に卒展に来られる方へ向けてのメッセージをお願いします。

◆卒制は学年全員の展示なので、全員の作品を見て欲しいです。

なんだかんだ気張った作品作っても「卒業」っていう言葉のなんか切なさが絶対あると思うんですよね。よろしくしてやってください。

◇楽しみです。ありがとうございました。

執筆:上田紗智子(アート・コミュニケータ「とびラー」)

2017.01.14

2017年1月13日(金)、学校向けプログラム「平日開館コース」が行なわれました。本日の参加は台東区の二つの小学校、谷中小学校4年生と忍岡小学校5年生のみなさん。東京都美術館で開催中の「TOKYO 書 2016 公募団体の今」を鑑賞しました。

プログラムの様子はこちら→

(「Museum Start あいうえの」ブログに移動します。)

2017.01.11

専攻は「美術教育」としながらも、アトリエにはたくさんの油絵が。今回お話を聞かせてくださった橋本大輔さんには、なんだかたくさんの秘密がありそうです。一体、どんな作品を描いているのでしょうか。

東京から電車で1時間弱、JRの駅からバスに揺られて15分。視界のひらけたおだやかな緑地に、東京藝術大学取手キャンパスは位置しています。寒さも厳しくなってきた2016年12月、卒展に向けて橋本さんのお話を聞くためにアトリエを訪れました。

■描いているのは、どんな絵?

アトリエの全体

-大きな絵! なんだか廃墟みたいですね。どこかに実在のモチーフがあるのでしょうか?

これは岩手県で、私のおじいちゃんの家の近くにある場所なんです。絵のモチーフには「空間」や「奥行き」のあるところに光が当たっている場面を選ぶことが多いのですが、特に廃墟だと屋根が破れて自然の光が差し込んでいるのが好きです。

-右手にパソコンやモニターが見えるのですが、デジタル技術とかも組み合わせているのですか?

そうですね。デジタルな写真技術を油絵に取り入れています。パソコンは画像の解析に使ったり、描くときにモチーフの詳細を見たりするのに使っています。

橋本さんが岩手で撮った、元の写真

-写真をもとに絵を描いていらっしゃるんですね。絵の方が、奥行きがあるような気がします。

それは、絵だと「積層」ができるからです。油絵の具には透明度があるので、重ねて塗ることで実際に光があたっているような表現ができます。でもデジタルな写真はそうではなく、すごく平面的な入れ子構図でできていますよね。そこに、あえて人間の認識を通して描きなおすことで、絵画として再び空間性を与えるということを行なっています。

-もとの写真は加工したりするのでしょうか?

いえ、ほとんどしていません。でも、奥行きをつけるために、絵を描くときに自分でコントラストをつけたりしますね。自分では、人間の認識を出力する機械みたいだな、と思っています。

-機械、ですか?

なんだか、絵を描いているのではなくて、パズルの組み立てのように絵の具を支持体に塗りつけているだけなのではないか、とつい思いますね。「いま、自分は絵を描いているのだろうか?」と考えながらいつも作業しています。でも、この思考の動きに興味があって、研究論文も自分の技法について書きました。「美術教育」といっても、私は学校教育ではなくて認知科学や表現技法の研究を専門にしています。

-理論と実践を同時に行なっているんですね。なんとなく「美術教育」のイメージがつかめてきました。

ええ、でも実際描くときは単純に「空間楽しいな」と思いながら描いています(笑)。例えば砂つぶひとつでも、絵画として空間を与えれば、表面をずっとなぞっていくことができます。面がいっぱいあるものをモチーフに選べば、自分が蟻になったつもりで、その表面をずっと辿っていける。そういった意味では、自分の絵には「地図」みたいな意味合いがあるなあ、と思いますね。

-描いているときは小さい生物になった気分で楽しめるんですね。

橋本さんが6年間使ってきたパレット

-こうして絵画の細かいところに着目すると、すごく面白いですね。

でも、作品全体として成り立つように心がけています。近くで見るというよりは、少し遠くから見て欲しいです。

-なるほど。そのほかには、見て欲しいところはありますか?

時間性に着目してほしいです。止まっている写真と、動いている光の間にある「ずれ」を画面に定着させることが重要だと感じていて。写真と絵の、時間性の違いを技法として表していけたら、と思っています。

-実際に展示室で見るのが楽しみです。

下塗りのキャンバスを触って、「ツルツル!」と嬉しそうなとびラー

■橋本さんと絵のカンケイ

-これまでの作品は、どんな感じだったのでしょうか?

だいたい似たような感じで、廃墟や光をテーマにしています。これが作品リストです。

-似ているのもあるけれど、こうして見ると雰囲気が違うものもありますね。

確かに、最初はネオン街などを描くことが多かったです。でも、人を描くのが嫌になってしまって、モチーフを廃墟にするようになりました。色もいらないやって思って、この頃は絵もモノクロですね。

-でもそこからまた、だんだん色が戻ってきていますね!本作では植物など、有機物もまた登場していますが、なにか変化があったんですか?

うーん、なにかあったのかなあ。自分のなかでは、変化していたら描き続けられてないんじゃないか、という思いがあります。でも、やっぱりこうして並べてみると絵には変化があるので、自分の変化を感じるために絵を描いている、という面もあるのかもしれないです。

橋本さんの作品リスト

-確かに、アウトプットがあって初めてわかることもありますよね。今描いているこの絵はもう完成に近いのでしょうか?

いまはまだ上層描きの段階なので、これからまた少し色味を足していきます。「早くやらなくては」という焦りもあるのですが、でもこの焦りって自分にしか存在しないものですよね。他の人からしたら全然理解できないものだと思うんですけれど、その状態がすごく面白いです。

-焦りも楽しめるなんて、すごい! 絵画の制作って、作業に終わりがないようにも思えるのですが、橋本さんにとっての「完成」はどんなときでしょうか?

私の場合は、元のデジタル写真に近づけることが完成なのだろうか、と思いながらやっています。あの画像にある、色空間の位置を全部把握して、ぴたぴた絵の具を置いていけばそれで終わりってわけでもなくて。だから、どこで止めるかまで含めてデザインですね。それが楽しいです。

-だいたい1日何時間くらい描かれているのですか?

朝8時から、夜の10時、11時とかまでですね。歯磨きと同じで、しないと不安というか。卒業したあとは非常勤講師などをしながら制作を続ける予定なのですが、今のようにたくさん時間がとれるわけでもないし、だから今は絵を描いている時間がすごく嬉しいです。

-ありがとうございました。

語り口は訥々としていながらも、会話の切れ端から絵に対する「楽しい」、「好き」という気持ちが強く伝わってきました。

卒展では大学美術館・地下に展示される予定の橋本さんの作品。彼の思いや絵に込められた「時間性」に思いを馳せながら、ぜひじっくりと鑑賞してください。

執筆:田嶋嶺子(アート・コミュニケータ「とびラー」)

2017.01.11

冬晴れの12月。彫刻棟の奥からさわやかに現れた吉野さん。第一印象は、長身で、まだどことなく無邪気さの残る学生さんというイメージでした。

木彫室へ案内され、ドアを開けた瞬間、広がってきたのは強い木の香り。

「これは何の木の香りですか?」と尋ねると、「クスの木です」とのこと。クスの木は彫刻によく使用される材料だそうです。スギの木とは違い、木が剥がれにくく粘りがあり、扱いやすいのが特徴だとか。どことなく懐かしい香りだと思っていたら、虫よけに使用されている「樟脳」もクスの木なんだそうです。他の木材との違いや特徴についても、丁寧に説明してくださいました。

そして、作業場の奥にある吉野さんの作品の前へ。

—卒業制作は、どのような作品なのでしょう?

「建築物みたいなかんじで、これまでに制作してきた作品が組み合わさってできています。西洋美術館にあるオーギュスト・ロダンの《地獄の門》をイメージしていて。全体としてはこれからもっと門のように組み上げられていく予定です。大学生活の集大成となる作品。」

すると、とても丁寧に穏やかなトーンで話されていた吉野さんから、

突然、衝撃的な言葉が飛び出しました。

「僕は、彫刻の乱暴なところとか、暴力的なところが気になっていて。」

「作品を作ることは、ある意味、暴力的な行為だと思っているんです。

切ったり剥がしたり、チェーンソーは絶対に人には向けてはいけないものなのに、木には使っている。木と木をくっつけたりつなげたり。作品を作る上では当たり前のことだけど、木からしたらすごく怖いことじゃないですか、こちらが気にしなくなっているだけで。」

—どうして「暴力」がテーマに?

「伝統的な技法にも、やっぱり暴力性は秘められていると感じていて。今回使用している寄せ木、千切り、かすがい、これらはまさにそうです。木を切って、打込んで。イメージを木を使って再現する際に、無理矢理かたちを変化させていって、理想的に仕立て上げるという嘘のあたりも暴力的だなぁと思っているんです。

彫刻って、イメージを作品にしたところで全く役に立たないかもしれないじゃないですか。やらなくてもいいことなのに、作家たちは夢中で、本来の目的から外れたとしてものめりこんで作業している。なかなか気付かないけれど、これってとても厳しいことなんじゃないかな。」

吉野さんの作品はとても大きな木彫作品で、カヤの木とクスの木を「千切り」「寄せ木」「かすがい」という伝統的な彫刻技法を使用してつなぎ合わせています。

【千切り】

【寄せ木】

【かすがい】

「たとえば、千切りは木のひび割れを止める為の技法なんですけど。「われるな、われるな」って。でも、それってばんそうこうみたいなものじゃなくて、ホッチキスの針みたいな強さのものなんですよ。そういう、木を自分の身体に置き換えた時に見えてくる暴力性だったり、突然大きなものが現れる暴力性だったり、全く関係のないものが持ち込まれたりする暴力性だったり…僕がこれまでに制作してきた作品もそんなテーマのものが多いです。美術には暴力的な行いが多く含まれていると思っています。」

「僕は基本的に嘘が嫌いなんですよ(笑)。大学に入る前に美術予備校に通っていた時期のことなんですけど、たとえばブロンズ像を見た時なんかにすごくかっこいいと思ったんです。でも、ある時裏側を見てみたら空洞だった。もちろんブロンズ像を軽くするための技術なんですけど、木彫作品でも内側をくりぬく技法があります。で、『自分が見ていたものはなんだったんだ?』って。

彫刻が『生きているようだ』と感じられるとしたら、それは魂の話じゃないですか。でも、そこには空洞がひろがっているだけで。実は目に見えている部分よりも、見えない部分の方が重要なんじゃないかって考えるようになった。だから、自分のやっていることを作品として、まずは嘘や暴力的なことの気持ち悪さや痛々しさを伝えようと思い始めたんです。そんな『嘘と暴力のかたまりである美術のままでいいのか?』と。」

「木を彫ることにも最初はすごく抵抗があった。やりたいという気持ちと、やってはならないという思いが、自分のなかで複雑に存在していて。でも、人に暴力的な行為を見せるためには、実際に自分でやらなければ、作品を作らなければ伝わらないと思った。行為も含めて見せつけなければ、僕の言いたいことは表現できないんだと」

—彫刻の理論と実践、両方を捉えているんですね。

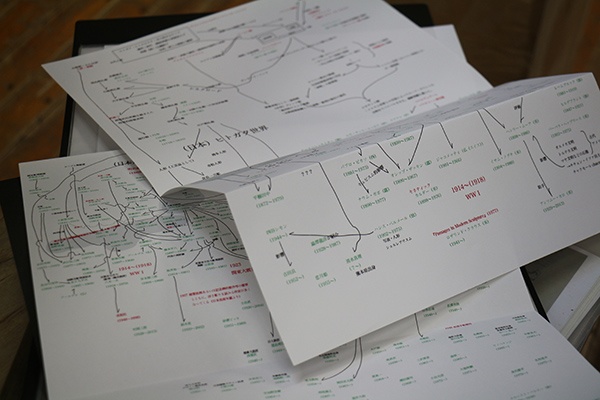

「『彫刻って何ですか?』と聞かれた時に、自分では説明がつかなくて。同級生でも、先輩でも、教授でも、人によって彫刻の定義はずれていたり、捉え方が全然違っていたりする。それで、彫刻史を研究して明治から昭和の作家が何をやっていたのかとか、さらにもっと昔の事を自分で調べて、ここはどこから影響を受けたのかとか、自分なりに図にしてみたんです。」

日本や西洋の彫刻の起源や、変遷について細かくまとめられています。

「教育分野にも興味があるんですが、彫刻を伝えるときに正しいことを教えられない、それこそ嘘しか教えられないというのがすごく嫌で。たくさんの要素が複雑にからみあう現状を、自分が彫刻をやっていくうえで、しっかり知っておきたいなと。

僕が作りたい作品のイメージは、このマップをベースとして、彫刻史全体のうえにのるような作品です。断裂された昔の考え方と、いまの考え方とを、全部包括するような作り手でありたいと思うんです。

彫刻って要素が複雑で。たとえば仏像にしても様々な様式があるし、sculptureという一言では言い表せないんですよ。その突破口がどこにあるかまだ全然つかめなくて、探しているところです。」

—いま大学四年生ですよね!?卒業後はどうされるんですか。

「大学院にすすんで、博士課程まで修了したいと考えています。自分の作品に関することだけでなく、彫刻というジャンル全体を見渡した文章が書けたらいいなと。ちゃんと言葉にして整理する時間が必要だと考えています。」

—そもそも彫刻をやろうと思ったきっかけは何ですか?

「親戚が寺に勤めていたこともあり、子供の時から仏像を見ていたので、もともと自分は仏師になろうと思っていたんです。もしくは保存修復の分野とか。でも、仏像や仏師の歴史について調べていたら、すごく曖昧で、不確かで。自分がやりたいことは何だったのかわからなくなってしまった。今は仏像をまともに彫るなどということは、自分はすべきでない、到底できることではないと感じています。」

「一度疑問を感じると、徹底的に調べたくなるんです。疑いの目線がすごく強くなって。『信じられるものは何か?』を追求してしまう。でも、調べると何も信じられなくなる(笑)」

「今回の作品は、自分が今まで作ってきた作品のパーツを寄せ集めて、組み上げ直しているんです。ばらばらの作品だったものを一つにまとめて。目指しているのは彫刻の『総合主義』です。いままでの歴史や、様々な事象を全て包含する作品。それもまた暴力的な考え方なんですけど。今までは寄せ木とか千切りとかの伝統的な技法を使いたくなかったんですけど、今回はむしろやらなきゃいけないなと思って。」

「今回は、一般の方というよりも、アーティストや彫刻家に向けたメッセージが強い作品です。僕は作家に対する作家という感じ。専門性が強くなりすぎてしまったかもしないけれど、わかりやすくシンプルに伝えようとすると抜け落ちてしまうことがたくさんある。」

「僕は展示の際、彫刻とともにテキストを一緒に置くことが多いんですけど。今回は作品だけを見せるつもりです。また、卒業制作展ではこのほかにも映像作品を展示します。嘘をテーマにした作品で、美術や彫刻がもつ虚偽の部分に焦点をあてています」

「よく芸術学に進んだら?って言われるんですけど(笑)。でも、文章を読んだり書いたりするだけじゃなくて、彫刻を実際に制作しているからこそ考えられることがあると思う。どれほどクリティカルにメッセージを伝えられるか、ということも大切だけれど、制作でしか伝わらないこともある。もちろん作品を作る上で、どう表現にもっていこう?と悩むこともたくさんあります。」

—見る人に向けて、伝えたいことはありますか。

「作品を見て、考えるときに、この作品はこうだ、あの作品はああだと、無意識のうちに自分の感覚で作品を切り捨てながら鑑賞することは多いと思う。でも、簡単に『見切る』のは良くない。どうしてこの作品は自分にとって良いと感じたのか、あるは良くないと感じたのか、なぜこのような表現になっているのか。切り捨てる前に、もう一度考えてから作品を見てほしい。考えることをやめないことが大切。」

広い視点をもち、真理を自分の「目」と「手」で確かめながら作品に向かう吉野さん。既成概念を鵜呑みにせず、自分で納得しなければ進めない性格については「めんどくさい奴ってよく言われます」と、笑いながらおしえてくれました。

吉野さんの目は、美術の世界に真摯に立ち向かう勇敢さと純粋さが織り交ざった深い目でした。インタビューを終えて、最初に出会った時のイメージとはずいぶん印象が変わったことを感じます。

聞き手のとびラーにとっても、生き方や物事のとらえ方、いろんな面で刺激を受けた、素敵な小春日和となりました。

吉野さんの作品は東京都美術館の地下ギャラリーに展示される予定です。今後の活躍も楽しみですね。

執筆:瀬戸口裕子(アート・コミュニケータ「とびラー」)

2017.01.08

インタビュー場所は東京藝術大学取手キャンパスの日比野研究室内パブリックスペース(と呼ばれているベンチとテーブルが置かれたスペース)。

今回のお相手は東京藝術大学先端芸術表現科修士2年生 今井さつきさんです。

藝大生インタビュー史上初、インタビューされる側の藝大生にコーヒーを出していただき、

和やかな雰囲気の中で様々なお話を伺いました。

■■■■■作品の話■■■■■

ー(テーブルの上のモックを見ながら)これが卒展の作品のイメージですか?山?

そうなんです。最初は山のイメージだったんですけど、途中で島に変化しました。中に人が入れる島です。

その中で物を作ったり、その人それぞれが自由に居心地よく入れる空間を作れたらと思っていて。体験型の作品です。

大きさは一番下の一辺が2mあって、直径4m、高さ2.6mです。

展示場所は大学(上野キャンパス美術学部)入ってすぐのところの屋外。

大学の入り口からいると「どーん!」と、この島が現れる予定です。

島には穴がついているので、外から覗いたりとか

中からひょこって人が出てきたりできる仕組みになっていて

中と外の人が交流できるようにしようと思っています。

見世物的な感じで誰かに見られながらワークショップを行うことにも価値はあるんですが、

今回はその人自身が自ら「何かをしよう」って思う気持ちを大切にしたくて、

外からはあまり見えない構造にします。

室内で作成したものが「これすごく良いかも」「誰かに見せたいかも」って

自分から思ったときに外に出てきて、そこで外にいる人と関わりたくなるような気分になればいいなと。

自分の中から引き出したものを、誰かに届けたくなる気持ちにさせる、

というのが自分の役割なのかなと最近感じていて、このような作品になりました。

■■■■■過去の話■■■■■

――なぜ体験型の作品を?

「人に体験してほしい」という学部生のころからのずっと変わらない気持ちがあって、

「体験ができる空間を作る」のが自分の作品のベースにあります。

私は藝大が3つめの大学で、最初に進んだのがビデオゲームなどの遊びを勉強する学科がある大学でそこで「遊び」について学んでいました。

元気がない人を見たとき、頭が「ぱんっ」ってするような楽しい体験をしてほしい思いがあって、どうしたら楽しくなれるのかを調べたときに「遊び」が効果的であることがわかって。

挑戦したり失敗したり、またもう一回トライできる「遊びの空間」に惹かれていって、体験できる、体験を作れる、なおかつ人とつながれる「遊び」の要素を学べるその大学に入りました。

そこではXboxのゲームとか作ったりしたんですけど、決められたプログラムの世界である電子機器のゲームに、私はちょっと違和感があって…。遊びの要素である「挑戦できる機会」とか「人とつながれる機会」は、もっと他に形にできるんじゃないかなと思って、卒業制作はゲームではなく、体験者の持ち物を万華鏡の姿に変換する作品(http://oxa-ca.jimdo.com/artworks/raybox/)を作りました。

そこに行かないと見られない、そこにいる人しか作れないっていう作品を制作することで、

その人の魅力だったり、またそれを人に見せることで誰かと関わったり、

人に見せたいな、という気持ちが生まれる機会を、アートのほうがうまく活用できるのはないかと気づいたのがこの時ですね。

卒業後は別の大学のデザイン科に進学しました。ここでは体験をすることで何ができるのかを模索した時期でした。そこで生まれたのが、人を「ノリ巻き」にしちゃう作品(http://oxa-ca.jimdo.com/artworks/human-sushi/)でした。

ロジェ・カイヨワという学者が唱えた遊びの定義というものがあって、

遊びは「競争、運、模倣、知覚が揺さぶられる体験」の4つの要素に分類されており、これらの要素がすべて自分の作品に詰まっていた。

ほとんどのアート作品はおそらく知覚的な体験の感覚があると思うんですけど、

知覚以外の遊びの要素を体験できる、そんな機会を与える作品を作っていきたいなと、あらためて気付いたんです。

今回の修了制作ではもう一度遊びの定義から見直して作っています。

■■■■■藝大の話■■■■■

-デジタリックなところから始まったのですね。現在の作品と真逆なので意外に思いました。

-その後藝大へ?

院を出たあとは1年くらい社会人をしていました。

でもやっぱりもう一度勉強したい、美術の人たちと関わる機会がもう一回欲しいなと思って、藝大の先端藝術表現科(以下:先端)へ進学しました。

先端はいろんな分野の人が来ますけど、私と同じ分野出身の人はいないので、

ここは自分の強みになるところですね。

藝大へ入学した頃は「ノリ巻き」のような作品を作っていこうと思っていたんですけど、なかなかうまくいかず・・・。大学院1年生のころは低迷していましたね。

自分の中で「体験ができたら作品になる」と思い込んでいて、

体験型の作品をいくつか作ったのですが、自分の中でピンと来ないものが続いて・・・。

その時は何でピントが合わないのか、何が足りないのか全然わからなかったんです。

悩みすぎて作品が作れなくなって、落ち込んでしまった時もありました。

そんなときに担当教員の日比野さんに「そういう時期はつくらないほうがいい」といわれ、

去年の秋から半年ぐらいは物を作らずに、人と話したり、飲んだりとか、自分がしたいことをしました。アートと何かをつなげないで、自分でただ普通に楽しむ生活を続けていた。

その後、TURNフェス(参考:http://turn-project.com/program/27)に参加して、

そこで初めて誰かと一緒に最初から作品を作って、

その作ったものをさらに他の誰かに体験してもらう、という経験ができたことで

新しい道が少し開けた感じがしました。

体験してもらうこと、人と一緒に作ってみること。

今までにはなかった、いろんな経験の幅を持つことができたので、「藝大に来てよかったな」と感じました。

■■■■■卒展に向けて■■■■■

-島の中ではどんなことをするのですか?

始めの構想では、島の中が花びらや花の形を作れる空間になっていました。

そこで作った花を外に持っていき、島の外側にさしていって、どんどん花の島になったらいいなと思ったんです。

よくわからない島の中にはいったら、洞窟になっていて、知らない人もいて

なんだか不思議な空間があって、でも何か作ったりする気持ちが自然と生まれるようになったらいいな、と考えています。

なぜ花を咲かせたいかというと、今年の夏にインドネシアのジョグジャカルタという古都に行ったときの、自分の価値観がひっくり返されるくらいの経験が元になっています。

ジョグジャカルタは不便なことがすごく多い田舎の地域で、ゴミの収集や給湯器など日本にいたら当たり前のシステムや設備がないんですけど、自然に合わせて人々が生活をしていたのが印象的で、「人がいることで都市が回っているんだなぁ」と強く思ったんです。

人が関わっていくことで、もともとあった像が変化していくのを作りたい、というのが夏ごろのイメージで、そのイメージがお花として残っています。

-もともとは土の島にするつもりだったんですね。

荒廃した島に、花が咲いて変化していくって話だったんですが、

「冬で上着を着ているのに、土の中には入らんだろ」という先生からの猛反発があって(笑)

実際は芝生の島になる予定です。

-見に来た人が入りたくなるかどうか、が大事?

自分の意見も大切ですが、それよりも体験してもらう人が居心地の良い空間を作るのも大切。自分の中でもう一度考えて、それだったら青々として興味が持てて、なおかつ入りやすい空間を、ということで土から芝生の島へ変わりました。

体験の「型」を作るからこそ、考えることですよね。

他の学生は自分の想いを作品に落とし込めていきますから、「どう見えるか、自分がどこまでこだわるか」が大事なんですけど、自分の作品は居心地がよくなるためだったら変えていくっていうことがあります。

—展示期間中に、今井さんは何をしているのですか?

私はいつも島の中にいます(笑)

大型の作品なので安全面的にも私が中にいたほうがよくて。

来てくれた人に説明とかもしますけど、一人で作りたい人はそっとしておく。

ふわーっと空気みたいな感じでそこにいたいです。

作品の世界の中で自分はバスドラムになれたらいいな、と。

目立たないんですけど、バスドラムは音に深みを与えていて。

私には気付かないけど、来てくれた人が居心地よくなれるよう。

―来る人のことを考えての作品作りですが、

―この作品の中で「ここは譲れない」というものはありますか?

外から見えない空間の中で、

誰かに伝えたいと思ったこと、誰かに見せたいと思ったものを

他の誰かに伝えたくなって外に出て交流できるための媒介として

私の作品が存在していたらうれしいです。そこが一番大切。

遊びによって挑戦したい、創造を試みたいって思える、

そしてそれによって誰かと関わることができる機会を作っていきたいです。

ずっと誰かに向けた作品を作ってきたのは、人が好きというのもありますね。

人と関わることをやるのが好きなので。

誰かと飲みに行ったりとか、どこかに出かけたりとか、

遠い地で新しい人に出会って「また遊びにおいで」とか「帰っておいで」って言われたりとか。

人と出会って話してっていうのが一番楽しい。

私の作品の根底には人と出会いたいっていう気持ちが強くあるのかもしれないですね。

―ありがとうございました!

執筆:小田澤直人(アート・コミュニケータ「とびラー」)

2017.01.08

本日お話を聞かせていただく、美術学部絵画科日本画専攻4年の石山諒(いしやまりょう)さんです。

■ アトリエ

日本画のアトリエは採光がよい大きな窓と真っ白な壁、掃除の行き届いた綺麗な床の部屋で、5人の学生の方々がそれぞれ畳2畳分はありそうな大きな絵を制作していました。

天井が高く、コンクリート作りの部屋は、夏は暑く、冬は寒そうで製作者には厳しい環境ではないかと思いましたが、膠の安定のために室温や湿度がある程度一定に保たれていて快適だそうです。

制作中の絵画すべてが床に置いてあり、絵画の上に木製の足場を渡し、その上に座って描いている方もいます。その理由は日本画独特の技法にあると石山さんが教えて下さいました。

——–床に置いて描くのはなぜですか?

「日本画は『岩絵具』という鉱物を砕いて作られた粒子状の絵の具を使います。その粉末を『膠(にかわ)』と混ぜ、描きます。そのため、油絵のように絵を立てかけて描くことができないのです。特に今回のように大きな作品の場合は真ん中付近は絵がかきづらいため、足場に乗りながら制作をします。」

■ 卒業制作作品について

深い重みのある緑が印象的な河原の景色、そのなかに数名の男性が描かれています。これからどうなるのだろうと次々と好奇心が湧いてきました。作品についてお話を伺いました。

「今回、卒業制作には自分と身近な人たちを描きたいと考えていました。」

——–描くために大切なことはなんでしょう?

「日本画はスケッチがとても大切です。今回も、何度も河原に行きました。」

貴重なスケッチも見せて下さいました。小さな部分は拡大図として描かれ、観察した時のメモも書いてあります。植物図鑑のような細かいスケッチです。

藝大に入学するまでの石山さんについて伺いました。

■ 日本画専攻を目指したワケ

——–子どもの頃から絵を描くことが好きでしたか?

「落書き程度ですが、幼い頃から絵を描くのは好きでした。近くの絵画教室にも楽しみに通っていましたが、絵を描くことよりも友達と遊ぶことの方が好きな普通の子供でした。ほかの友達に比べて絵をかくことが得意などといった、絵に関して特別なことはなかったように思います。」

——–芸術系という進路はいつ頃決めましたか?

「高校2年生の時に美大受験を決め、夏から美術予備校に通い始めました。その頃はデッサンが本当にヘタクソでした。」

——–東京藝大受験で日本画専攻を選んだ理由を教えて下さい。

「予備校でデッサンの練習を続けていくうちに、より描写する技術について学びたいと考え、物の描写に力を入れている日本画科を目指すのが一番だと思ったんです。藝大入学後はどの人もみんな絵が自分より上手で圧倒されました。下手な人が1人もいないので見ていて楽しかったです。」

——–藝大の4年間で一番印象深いことは何ですか?

「深く印象に残っているのは古美術研究旅行です。奈良の寺社仏閣をめぐり、普段は目にすることができない貴重な作品をたくさん見ることができ、素晴らしい体験でした。」

次に、日本画ならではの制作の特徴についてお話を伺いました。

■ 日本画の制作の特徴

・準備と下書き

① 和紙は水張りや裏打ちなどをして描けるように準備をします。

② スケッチ…まずは描きたいものをよく見てスケッチします。日本画は大きな修正をしにくいのでよく考えて丁寧にスケッチをします。

③ 転写…スケッチしたものをトレーシングペーパーで写し取り、捻紙で和紙に写します。

④ 骨描き(こつがき)…転写したものを墨で線描きすることを言います。

このように絵の具を使うまでに少なくとも3回下書きをすることになります。

・絵の具と膠(にかわ)

次に岩絵の具と膠(にかわ)です。

アトリエでは、1人ひとつずつ道具箱を持っています。これは石山さんの道具箱です。引き出しにはいくつもの岩絵具が入っていました。鉱物を砕いて粒子状になったものは小さなビニールパックに入っています。号数は粒子の大きさを示し、細かくなるほど仕上がりが白っぽくなります。天然の岩絵具はどれもとても高価なので、手ごろな新岩絵具というものもよく使うそうです。

これらの岩絵具は膠(にかわ)という接着剤と混ぜて和紙に着彩していきます。

・盛り上げ技法

よく見ると、作品の白い部分だけ盛り上がっていることに気付きました。これは「盛り上げ技法」という特別な技法で描かれたものです。貝殻を砕いて作った「胡粉(ごふん)」という白色の岩絵具を使います。

確かに和紙から数ミリは高く盛り上がっており、ロウ石のようにすべすべしています。

■ 普段の生活について

現4年生の日本画専攻は25人中男子10名、女子15名。雰囲気も良いようで日本画用の和紙の裏打ちや作品の搬出などもお互い協力してやることも多いと聞きました。石山さんのアトリエも、制作の合間には5人でおしゃべりを楽しむなど仲間の笑顔も印象的な和気藹々とした雰囲気でした。

——–今まで描いた作品はどうなさっていますか?

「作品は全て大切に保存しています。普段は木枠を付けません。日本画の性質上、丸めて保存する事が出来ないのでそのまま置いてあります。」

執筆:東悦子(アート・コミュニケータ「とびラー」)

2017.01.08

11月末、銀杏の葉が秋晴れの上野の空に映えている中、東京藝大を訪れました。今回、取材に応じて下さった藝大生は、工芸科漆芸専攻4年生の大崎風実さん。樹木の生い茂った工房棟の前で待ち合わせしました。時間ぴったりに来てくださった大崎さん、まずは、卒業制作の作品が置かれている場所に案内していただきました。

〈卒業制作の作品。私の予想をはるかに超えた大きな作品でした。躍動感にあふれ、美しいフォルムで、圧倒的な存在感を感じます。これが漆芸品とは!〉

★卒業制作について

「5月頃より先生たちとディスカッションをしながら、作り始めました。スケッチをしたり、小さな模型を作ってみたりして、夏休み頃から漆の仕事を始め、今に至っています。これは乾漆造形という技法を使っています。有名な阿修羅像もこの技法になります。発砲スチロールで原型を作り、それに麻布をまいていって固めて、漆を塗ります。塗って乾かせ、乾いたら少しずつ研ぎだしていきます。まだ制作途中で、これから磨き上げ、金や銀で絵を描く予定です。下地の工程から考えるとおおよそ25工程位あり、大変時間がかかります。」

〈まだ制作途中とのこと。さらに磨きこまれたら、どんなふうになるのでしょうか?ますます完成が待ち遠しいです。〉

「タイトルは《走レ》です。雨降る暗闇の中を走るオオカミをイメージしています。卒業制作に向けて緊張したり悩んだりといった不安や葛藤と、作ったらよいものができるのではないかという希望と、その相反する二つの思いを、二匹のオオカミで表しています。その二つの思いが入り混じりながら走って、私の中の大きなエネルギーとなることを表現していきたいと思っています。私自身、小さい頃からオオカミを絵に描くことが多くありました。オオカミは一見こわそうに見えるけれども、寂しそうにも見えます。鳴き声もこわそうだけれども、切なそうにも聞こえてきて、とても魅力を感じました。一匹オオカミと言うけれども、群れていないと生活できず、まるで人間みたい、私みたいだなと思いました。」

〈命のエネルギーを形にしている大崎さん。そのプロセスは日々自己との葛藤なのではと想像しました。目に見えないものを目に見える形にしていくということがとても素晴らしいと思いました。〉

「体の表面に粒粒しているのは螺鈿です。漆黒の闇の中、降る雨を螺鈿で表しました。螺鈿の箱を見て、つやつやしてキラキラした感じから雨の粒をイメージしたからです。目は七宝を別に作ってはめ込んでいます。この七宝も自分で作りました。」

〈大崎さんの許可をいただき触ってみました。思っていたよりずっと柔らかく繊細な感じがしました。〉

★漆芸について

「父の実家が京都にあり、小さい頃より漆の工芸品が身近にありました。お正月になると、漆塗りのお重の蓋を開け、漆塗りのお椀を手に取り、美しさを感じていました。また茶道を習っていて、棗を目にする機会もあり、漆芸品に魅力を感じていたことが、この道を選択した大きな理由だと思います。東京藝大では、工芸科に入り2年間幅広くいろいろな工芸を勉強しました。3年生より漆芸を専攻し、漆芸の基礎的な技術や技法を学んできました。4年生ではその技術や技法を使って、卒業制作に取り組んでいきます。さまざまな技法によって多彩な表情が生まれるので、表現したいものによって技法が変わっていくと思います。」

〈工作室。機材がたくさんあって、木を切ったり模型を作ったりといろいろな作業をする所だそうです。このあたりから、漆の香りが立ち込めてきました。〉

〈作品を乾燥させている所。湿度の調整がとても大切とのことです。もう一頭のオオカミは、フォルムも表情も違っていて、早く二頭並んで疾駆している姿が見たいです。〉

「漆の作品は、正倉院に中にも保存されています。日本だけでなく中国でも韓国でも盛んです。ベトナムでも漆が採れ、漆絵として人気です。漆は装飾的に使われるだけでなく、元来道具に塗って、物を強固にする塗料として使われたそうです。漆の魅力はと問われれば、自然のものだから美しいと言うことでしょう。木の樹液が、命のパワーを作ろうと思っていることにマッチしているのではないでしょうか。素敵な素材だなと思います。漆という素材を生かして作りたいと思う物が、どんどん自分の中にあふれてきます。今回の卒業制作もそうですが、漆を塗り重ねることによって私が作りたいものになっていくのではないかと思いながら、制作している最中です。漆をこれからも使い続けていきたいと思います。」

〈漆と大崎さんとの間には自然な空気感があるようでした。〉

〈大崎さんの作業机の上。今回の卒業制作の小さな模型が見えます。〉

〈小さい手板で実験的にいろいろな技法を試みた作品。手板を一枚ずつ見せていただくごとに歓声をあげてしまうほど、その美しさと豊かさに魅せられてしまいました。〉

★これまでの歩みと大学生活について

「小さい頃から絵を描くのが好きで、物を作ったりするのも好きでした。絵画教室に通ったり、絵日記コンクールに出品したりもしました。母が美大出身で、同じ道を歩いてきているので歩きやすかったと思います。美大に進むことを意識したのは高校生の時です。多摩美大の工芸科に入ったのですが、漆芸専攻がなかったので、漆芸をやりたいと思い、東京藝大に来ました。今は卒業制作中心の毎日ですが、切羽つまっていない時は、普通の女子大生です。バイトをしたり、学校から離れて作りたいものを作ったり、展示を企画したりしました。大学生活では、1年生の時に藝祭で神輿を作ったことが印象深いです。また大学の先生方の制作している後ろ姿を見ながら勉強できたのは、私にとって大きな財産でした。先生たちも生徒と同じように作り続けています。その先生方の作家性にふれるたびに感動しました。同級生との声のかけ合いや刺激のし合いもモチベーションにつながったと思います。そして、やりたいことや作りたいものを全面的に後押ししてくれる家族に感謝しています。」

〈周りの人々から多くを学び受け取り、それを糧に自己の作品に対する表現力を磨こうとする大崎さんの姿勢を感じました。〉

★これからについて

「大学院に進んで、もう少し勉強したいという気持ちがあります。それは作家性を強めたい、将来作家になりたい、という思いからです。そのためにもっと勉強する必要があると思い、大学院への進学を希望しています。工芸品は手間のかかるものです。木地を作る職人さん、漆を塗る職人さん、蒔絵をする職人さん・・・とたくさんの工程に分かれて仕事をしています。全部自分でやろうとしても、1年2年では習得しきれません。大学院に行ってからもっと練習したいと思っています。将来にわたり、物を作り続けていきたいと心に刻んでいます。技術的なことを高めていき、自分のできる幅を広げていくことももちろん必要です。けれども、見えない命のエネルギー、うまく言葉で言えないものを形にすることを、自分の中でもっと突き詰めていきたいと思っています。」

お忙しい中、どんな質問にも一つ一つ言葉を選びながら、丁寧に答えてくださった大崎さん。その誠実なお人柄と制作に向かう真摯な態度が作品にも表れているようでした。大崎さんの言葉の中に、工芸は「こつこつ」「繰り返し繰り返し」「同じことをずーっと」「我慢しながら」続けるとありました。だからこそ、「真面目で意思がないとできない」とも。大崎さんは、その言葉を実践されているのだと改めて気づきました。是非、物を作り続けていってほしい、漆の美しさを表現していってほしいと願っています。

大崎さんの作品は、東京都美術館ギャラリーCに展示されるとのことです。大崎さんも作品のお近くにいらっしゃるそうです。早く見に行きたいですね。会いに行きたいですね。

執筆:鈴木優子(アート・コミュニケータ「とびラー」)