2012.06.23

After the last Foundation Course ended, we had meeting and closing party for the Foundation Courses at the Restaurant Ivory in the Tokyo Metropolitan Art Museum from 6 o’clock in the evening. With the conclusion of all six Foundation Courses, the TOBIRA candidates (hereinforth: TOBIKO) had developed quite good relationships. I think the Foundation Courses were quite difficult, but everyone worked hard.

All the members of the TOBIRA Band, who I previously introduced in this blog, also appeared. They performed the well-known NHK song “Metropolitan Art Museum” because the Tokyo Metropolitan Art Museum is a Tokyo Metropolitan Museum. The TOBIRA Band performance in the costumes with the matching blue turbans made by Tokita-san, one of the TOBIKO, were like a symbol of the work completed in the two months since the TOBI Gateway Project began.

This “Girl with a Pearl Earring” is Ōhashi-san, the supervising curator of the Mauritshuis Gallery exhibition. It looks quite good on her! Also, taking the timing into consideration, I’d really like to have a meeting of all TOBIKO. Next up are the Practical Courses. Let’s all do our best! (Itō)

2012.06.23

The Foundation Courses, six classes in all, finally held the last session. The instructors for this class were curators Ms. Sawako Inaniwa, Ms. Yumi Kono, Ms. Natsuko Ohashi, and myself, Tatsuya Itō. At the beginning, Ms. Inaniwa and I once again reviewed the summary of the art communication that the Tokyo Metropolitan Museum (hereafter: TOBI) aspires to.

As this was the last one, everyone was more serious than ever in class.

Over the period of the Foundation Course from this April to June, we asked the TOBIRA candidates (hereafter: TOBIKO) to choose at least one program out of the following: “School Monday (School Collaboration: Art Viewing through Conversation),” “Architecture Tour,” and “Access Program (Supporting Special Viewing Events for the Disabled)” and decide the general direction of their future activities. The TOBIKOs must attend at least 80% of their chosen program’s Practical Application Courses. And we strongly recommended they take on a leadership role of the program in the year after completion of the Courses.

In order to share the characteristics of each program, we had the curator in charge of each explain the details. Ms. Kono, the curator in charge of the “Architecture Tour,” went first. The Architecture Tour Practical Application Course has already started, and it has been mentioned in this blog as well. This program plans tours to introduce the Tokyo Metropolitan Art Museum, a building created by Mr. Kunio Maekawa, an exemplary Japanese architect who studied under Le Corbusier. Rather than stereotypical architectural tours, we are aiming for architecture tours full of originality created by each individual TOBIRA.

Next, Ms. Ohashi provided us with an explanation of the “Access Program (Supporting Special Viewing Events for the Disabled).” At TOBI, we schedule Special Viewing Events for the Disabled three times a year. Utilizing the days the Museum is closed, the TOBIRAs set up a day for people with disabilities to view the art pieces safely and with ease. The first special viewing for the disabled is the “Masterpieces from the Royal Picture Gallery Mauritshuis,” where Vermeer’s “Girl with a Pearl Earring” is displayed.

Lastly, came Ms. Inaniwa, who is in charge of the “School Monday (School Collaboration: Art Viewing through Conversation)” project. This is a program to offer TOBI as a place to practice art viewing education in collaboration with elementary and middle schools. Since there are many visitors normally, we utilize the days that the museum is closed and offer conversational viewing education that centers on VTS (visual thinking strategies) for special exhibits for which it is difficult to offer practical viewing education.

“School Monday (School Collaboration: Art Viewing through Conversation),” “Architecture Tour,” and “Access Program (Supporting Special Viewing Events for the Disabled)” are three pillars that support the activities of the TOBI Gateway Project. Also, even outside the activities of the program they selected, we recommend that people step out of the framework of the program and participate such as when there is not enough staff, when we are in need of more support, or when the subject is extremely interesting to them.

In addition to an explanation of these three main programs, the morning Foundation Course ended by going over TOBI’s exclusive information sharing systems, including our mailing list, the “TOBI Gateway Project Bulletin Board,” and “Today’s White Board.” For anyone outside of the TOBI Gateway Project that keeps up with this blog, you might have noticed the banner at the top of the homepage that says “TOBIRA Private Bulletin Board.” When you click it, two banners show up: “TOBI Gateway Project Bulletin Board” and “Today’s White Board.” Unfortunately, you will not be able to see anything beyond this point unless you are a TOBIKO. Actually, the system beyond this point has TOBIKO meeting minutes uploaded with each White Board picture, post-meeting impressions and additional information. There has already been lively activity beyond our expectations.

In the afternoon, under my facilitation, each TOBIKO gave a presentation on a number of new projects they are managing which are presently underway. There are already more than 10 projects that can only come from the perspective of a TOBIKO, such as the “TOBIRA Band,” where TOBIKO who can play instruments and get together to perform; the “TOBIRA Information Department,” where TOBIKOs aim to share and disseminate information about TOBI and the Tokyo National University of Fine Arts and Music through newspapers, blogs and other media; and “Map & Manual,” where they create TOBI maps and think about knowledge sharing to support TOBIRA activities. By carefully presenting the projects one by one, they discovered projects that could help each other, and asking questions lead to the birth of new ideas – it was a very productive presentation time.

The projects have only just begun, so their realization of each project depends on the efforts of the TOBIKOs. Every TOBIRA staff member would like to support the TOBIKOs as much as possible.

That’s the way I was feeling. But on the other hand, as a project manager, I believe that the TOBIKOs sharing and discussing thoughts and ideas using the activities they came up with from their own viewpoints as a trigger is an asset and a very important process for the growth of the TOBI Gateway Project. (The “Power of Listening” makes this possible.)

What connects approximately 90 TOBIKOs – people whose ages and occupations vary – is the platform called “art.” Of course, I believe that there are many platforms other than art that can hold people’s various values. However, there seems to be no other platform that can so lightly transcend yet widely and flatly embrace such diverse genders, ages, occupations, and value systems, in the way that art can. Since art is a framework for incomparable possibilities, I believe that art can function as a convertible medium in establishing community. (Perhaps art has such a timeless, universal appeal and value in and of itself that it can become such a large frame.)

By defining art as our platform, a large variety of TOBIKOs can work in harmony and build trusting relationships – something which we believe builds the backbone of the TOBI Gateway Project.

Oftentimes people use analogies like “Art is the backbone of society” or “Art will produce effects on society gradually, like Chinese medicine.” If art exists as the platform to support people’s wide variety of values, it must indicate that social capital (social capital: the idea, proposed by American sociologist, Robert Putnam that various people interact and build relations itself is the base of society’s capital) is stored at a high level in the society (community).

Even for the TOBI Gateway Project, the accumulation of social capital is a high priority. Showing the understanding of differing value judgments, building trust beyond such characteristics as age and social status, and more than anything, if you are not able to build relationships where you can share such things as your problems, risks, difficulties and failures, then you cannot truly say that social capital is accumulating in the TOBI Gateway Project.

Also, this discussion does not just end with the TOBIKOs. We absolutely want this capital stored up amongst the people who work in various capacities at TOBI. Basically, we would like to save up social capital within TOBI. In fact, the essence of this year’s TOBI Gateway Project activities lies there. If we do not create a strong backbone in the TOBI community by building a stock of social capital, the image of TOBI as a social device that “forms an open and practical community promoting communication through art with the Museum as a base” – will be nothing more than a dream. Although the expectations for the TOBIKOs will only grow, that’s okay. I am sure that the members will be able to meet these expectations because our intent was to pick TOBIRA candidates with the “perseverance to engage in dialogue and the power to treat it with sincerity.” (We also felt that the longtime volunteers supporting the Special Viewings for the Disabled before the Museum closing share these qualifications as well, so we made them become TOBIRA candidates as a group.)

Lastly, we got to provide technical advice to the TOBIKO to make progress on their projects going forward. First, the instructor Nishimura-san went over the written contents of the “TOBI Gateway Project Bulletin Board.” After that I offered my own advice. These are some points needed to turn your enthusiasm into a driving force. I think results will change drastically just by keeping them in mind.

Three points from Nishimura-san:

1. In any type of project, it is good to share a way to end it or an image of its dissolution at the beginning. For example, “we will dissolve when we achieve xxxx,” or set a time limit with “automatic dissolution at such and such a time,” and so on. When the time comes to dissolve, if there is still a feeling of “Let’s keep working!” then you can start on point 2.

2. Experiences such as where you keep encountering pointless connections, should you just automatically dissolve or evaporate? Since this won’t affect the relationship positively in the future, it is good to share a way to dismiss at the beginning. When you dissolve, everyone should have fun!

3. You shouldn’t use a system of “throwing ideas out there and waiting for people’s responses.” Go as far as you can on your own.

Itō’s 3 points for having a meeting (+1 extra)

1. Quantify the image (specify the schedule and amount of money, etc.).

2. End the meeting by switching to tasks (jobs).

3. Think about a balance between the amount of work and the collection of results. (It may not apply to the TOBI Gateway Project, but people often say “The result would have been the same even if we had not put together that document…” It is pointless to get satisfaction from making the document.)

+1 And the most important thing – Share your workload before it gets too rough and makes you feel like “I can’t handle this!” The most important thing is to “send” and “receive” warnings.

After the last Foundation Course ended, TOBIKOs voluntarily divided themselves into a variety of self-run planning groups and met until the evening. Amazing! This photo depicts them in wheelchairs checking Museum accessibility for the disabled.

All six Foundation Course classes have now finished. Now we will move onto the Practical Application Course. It’s going to be the real thing from now on! (Itō)

2012.06.23

基礎講座最終回が終わった後、夕方6時から、東京都美術館内にあるレストランIVORYにて、基礎講座の打ち上げを兼ねた懇親会が催されました。全6回に渡る基礎講座も全て終了し、とびらー候補生(以下:とびコー)同士もかなり仲良くなりました。なかなか厳しい基礎講座だったと思います。みなさん大変お疲れさまでした。

以前、このブログでも紹介した「とびら楽団」のみなさんも登場しました。演奏して頂いた曲はNHKみんなのうたでおなじみの「メトロポリタン美術館」です。東京都美術館も東京メトロポリタンミュージアムなので。とびコーの時田さんがつくってくれた衣装とお揃いの青いターバンを身につけたとびら楽団の演奏は、とびらプロジェクトがはじまってからこの2ヶ月間の充実した活動を象徴しているかの様でした。

こちらの「真珠の耳飾りの少女」はマウリッツハイス美術館展の担当学芸員の大橋さん。かなり似合ってます!また、タイミングをみてとびコーさんが全員揃う会を是非開催したいですね。これからは実践講座です。みなさん頑張りましょう。(伊藤)

2012.06.23

全6回の基礎講座もついに最終回を迎えました。今回の講師は学芸員の稲庭彩和子さん、河野佑美さん、大橋菜都子さん、それと僕、伊藤達矢です。はじめに、稲庭さんと僕からもう一度東京都美術館(以下:都美)の目指すアートコミュニケーション概要についておさらいさせて頂きました。

最終回だけあり、みなさん何時にも増して真剣に受講されていました。

この4月から6月にかけて行われた基礎講座の期間中に、とびラー候補生(以下:とびコー)のみなさんには、「スクールマンデー(学校連携:対話を通した作品鑑賞)」、「建築ツアー」、「アクセスプログラム(障害のある方のための特別鑑賞会サポート)」のプログラムの中から必ず1つ以上選択して頂き、今後の活動の大きな方向性を決めて頂きました。選択したプログラムについては、該当するプログラムの実践講座を8割以上出席し、次年度からはそのプログラムのリーダー的存在になって頂くことを強く推奨しています。

そこで、それぞれのプログラムの特色を共有するために、それぞれの担当学芸員さんにプログラムの詳細を説明をして頂きました。はじめは「建築ツアー」担当学芸員の河野さんから。建築ツアーは既に実践講座がスタートしており、このブログでも紹介済ですが、コルビュジェに師事した日本を代表する建築家前川國男の作品である東京都美術館を紹介するツアー企画です。ステレオタイプの建築ガイドではなく、とびラーひとりひとりがつくるオリジナリティー溢れる建築ツアーを目指しています。

続いて、「アクセスプログラム(障害のある方のための特別鑑賞会のサポート)」については大橋さんからご説明を頂きました。都美では「障害のある方のための特別鑑賞会」を年に3回予定しています。休館日を使い、障害のある方にも安全に安心して作品を鑑賞してもらえる日をとびラーがつくります。初回の「障害のある方のための特別鑑賞会」はフェルメールの「真珠の耳飾りの少女」が展示されるマウリッツハイス美術館展です。

最後は「スクールマンデー(学校連携:対話を通した作品鑑賞)」担当の稲庭さん。小中学校と連携した鑑賞教育の実践の場として都美を開くプログラムです。普段は来館者が多いため、鑑賞教育の実践が難しい特別展を、休館日を活かして特別開館し、VTS(ヴィジュアル・シンキング・ストラテジー)を中心とした対話型鑑賞教育を実施します。

「スクールマンデー(学校連携:対話を通した作品鑑賞)」、「建築ツアー」、「アクセスプログラム(障害のある方のための特別鑑賞会サポート)」はとびらプロジェクトの活動を支える3本柱となるプログラムです。そして、自分が選択したプログラム以外の活動であっても、人手が足りないときや、力を合わせなくてはならないとき、凄く興味のある内容のときなどは、プログラムの枠を超えて参加することをお勧めしています。

午前中の基礎講座は、この3本の主要プログラムの説明に加え、メーリングリストや「とびらプロジェクト掲示板」「本日のホワイトボード」などの専用情報共有システムについて確認したところで終了しました。とびらプロジェクト関係者以外の方でこのブログをご愛読頂いている方がいれば、きっとホームページ上のバナー「とびラー専用掲示板」にお気づきになった方もおられるかと思います。クリックすると「とびらプロジェクト掲示板」「本日のホワイトボード」の2つのバナーがでてきますが、残念ながら、ここから先はとびコーさんでないと見ることができません。実はこの先のシステムはとびコーさん同士のミーティングの記録がホワイトボードの写真ごとアップされていたり、ミーティング後の感想などや追加事項などがアップされていたりします。既に想像を超えて活発な活用が展開されています。

午後は、僕のファシリテートのもと、現在進行中の数々の新規プロジェクトのプレゼンテーションを担当のとびコーさん自身からして頂きました。楽器が出来るとびコーさんが集まり演奏を行う「とびら楽団」、新聞やブログなどを通して都美と芸大の情報共有と発信を目指す「とびら情報部」、とびラーの活動を支える為の都美のマップ作成と知識の共有を考える「マップ&マニュアル」などなど、とびコーさんの目線ならではの企画が既に10個以上立ち上がっています。一つ一つの企画を丁寧に発表して行くと、思わず助け合える企画同士を発見できたり、質問に答えているうちに新しいアイディアが生まれたりと、非常に実のあるプレゼンテーションの時間でした。

一つ一つの企画はまだ芽を出したばかりで、実現できるか否かはとびコーさんらの頑張り次第なところもありますが、とびらスタッフ一同、出来る限りとびコーさんたちをサポートして行きたいと思います。

また、そういった思いもある一方で、僕はプロジェクトマネージャとして、とびコーさんたちが自分たちの視点から生まれた活動をきっかけに、思いや理想をお互いに語り合うこと(共有すること)の方が、とびらプロジェクトの成長過程にとって非常に重要なプロセスであり財産だと考えています。(それを可能にするのが「きく力」なのです。)

年齢も職業もバラバラな凡そ90人のとびコーさんたちを繋いでいるのは、アートというプラットホームです。もちろんアートでなくとも、多様な人々の価値観を乗せるプラットホームは存在すると思います。しかし、性別や年齢、職業や価値観を軽やかに越境し、広くフラットに包み込むことの出来る類希なフレームはアートをおいて他に見当たらず、比類ない可能性を持ったフレームだからこそ、アートはコミュニティーに変換可能な媒体として機能できるのだと思います。(時代を超えた普遍的な魅力や価値がアートには内在しているからこそ、きっとこれだけの大きなフレームになりえるのでしょう。)

そして、アートをプラットホームとすることで、多種多様なとびコーさんたちが協調し合い、信頼関係を積み上げることこそ、とびらプロジェクトの”背骨”をつくることに繋がると思っています。

よく「芸術(アート)は社会の背骨である」とか、「芸術(アート)は社会にとって漢方薬のようにじんわり効能を発揮する」といった例えられ方をします。それは、芸術(アート)が人々の多種多様な価値観を抱える大きなプラットホームになることよって、ソーシャル・キャピタル(社会関係資本:多様な人々が関わり合い、関係性を築くこと自体が社会の資本となり得るという概念)が、高い水準で社会(コミュニティー)に蓄えられた状態を指し示したものに他なりません。

とびらプロジェクトにとっても、このソーシャル・キャピタルの蓄積は至上命題です。異なった価値観に対して理解を示し、年齢や立場を超えた信頼を築くこと、そしてなによりも問題やリスク、困難や失敗をも共有することのできる関係を構築して行くことができなければ、本当の意味でとびらプロジェクトにソーシャル・キャピタルが蓄えられたとは言えません。

そして、これはとびコーさん同士で終わる話ではなく、都美で働く様々な業種の方々との間にも是非とも蓄えて行きたい資本であると思っています。つまり都美の中にソーシャル・キャピタルを蓄えて行きたいと考えています。むしろ、今年のとびらプロジェクトの活動の本質はそこにあると思っています。ソーシャル・キャピタルを蓄え、都美というコミュニティーに強靭な背骨をつくってゆかなければ、「美術館を拠点に、アートを介したコミュニケーションを促進し、オープンで実践的なコミュニティーを形成」する社会装置としての美術館の姿など到底夢のまた夢。。。とびコーさんにかかる期待はますます大きくなるばかりですが、大丈夫、このメンバーなら成し得てくれることでしょう。なぜなら「対話をすることの粘り強さと、誠意をもって接する力」を持つ方々をとびラー候補生として選出したつもりだからです。(休館前に障害のある方々の特別鑑賞会のボランティアを長らくされていた方々にも、そうした資質は共通していると感じて、ひとまとまりのとびら候補生となって頂きました。)

最後はこれからとびコーさんたちが企画を進行させて行く上での、テクニカルなアドバイスをさせて頂きました。はじめは、講師の西村さんが「とびらプロジェクト掲示版」に書き込みした内容のおさらい。その後は僕からのアドバイスです。意気込みをしっかりと推進力に変えて行くために必要な幾つかのポイントです。ちょっと気を付けておくだけで、結果は大きく変わるかと思います。

2012.06.19

2回目の建築ツアー実践講座が行われました。今回は主に、東京都美術館(以下:都美)の建物の特徴や歴史について学びました。講師は学芸員の河野さんです。とびラー候補生(以下:とびコー)が現場に立ってツアーガイドを行うときに知っておきたい基礎知識を中心に、ちょっとした裏話しまで幅広く講義して頂きました。スライドの写真は都美の父ともいわれる九州の炭鉱王佐藤慶太郎氏。当時の100万円(現在の33億円程度)を東京府に寄付し、1926年(大正15年)に東京府美術館(現 東京都美術館)が開館する礎を築いた方です。

2012.06.19

The 2nd Practical Application Course on Architectural Tours was held. This time, participants mainly studied the characteristics and history of the Tokyo Metropolitan Museum (hereafter: TOBI) building. The instructor was the curator, Ms. Kono. She mainly lectured about the fundamental knowledge that TOBIRA candidates (hereafter: TOBIKO) would want to know when guiding a tour on-site. She also lectured on a wide range of topics, including a little behind-the-scenes story. The photo on the slide is of Keitaro Satō, the king of coal mines in Kyushu, also known as the “father of TOBI.” He donated 1,000,000 yen at the time (approximately 3,300,000,000 yen today) to the City of Tokyo and contributed to the opening of the Tokyo Museum (Now, Tokyo Metropolitan Art Museum) in 1926 (Taishō 15).

The old Tokyo Museum built with the donation from Mr. Keitaro Sato was forced to rebuild over time. In 1975, the migration from the old Tokyo Museum to the current Tokyo Metropolitan Art Museum designed by Mr. Kunio Maekawa was completed. Surprisingly, they built a new building right next door while they were running the old one – it was like an acrobatic transfer. Also, Mr. Maekawa worked on the design of the Tokyo Bunka Kaikan [cultural hall] in Ueno Park, and the National Museum of Western Art, located on the opposite side, is a piece by his mentor, Le Corbusier. On the other hand, natural scenery such as Shinobazu pond and the Musashino primeval woodland remain in Ueno Park. Construction of TOBI was carried out under Mr. Maekawa by fusing this varied beauty while paying respect to the environment of the entire park surrounding the museum building.

Additionally, once you look inside, the TOBI building has various creative things hidden that people normally do not notice. For example, the handrail on the stairs inside the Museum has been processed so that all of the corners are removed and rounded. This is because when TOBI was built back in the early 1970s, many of the Museum visitors still wore kimonos. It was designed to prevent kimono sleeves from getting caught on the handrail. We can still see this, even after the renovation. Beyond that, there were many things that made us admittedly nod our heads in recognition of their creativity, such as the “snagging process” creating the impression of soft light and shadow from the indentations made on a once beautifully hardened concrete surface and the tile placing method which makes the outside wall covering TOBI look like bricks at first glance.

One memorable historical episode is the story of a large slanted gash that still remains on the concrete at the TOBI main entrance. In the early ’70s, when TOBI was under construction, Japan faced an oil crisis. As a result of this, there was a state of panic when a concrete mixer could not arrive during the construction of the entrance. The concrete to replenish the supply was never delivered, and the already added concrete had started to harden. As a result, the outline of the break remains deeply visible. It is said that the person in charge at the site kneeled down on his knees to apologize for the mismanagement to Mr. Maekawa, but he simply responded “This is a scar of the times. It looks like the ridge line of a mountain; I think it’s fine as is.” It’s an intriguing story.

Stories about TOBI never end. Currently, the TOBIKOs are studying for the upcoming architecture tour. The next Practical Application Course on Architectural Tours is still a month away. Until then, the homework for the TOBIKOs is to create our own tour plan. I am really looking forward to the tour ideas that will emerge. (Itō)

2012.06.09

The theme of the 5th Foundation Course is “Research on How TOBIRAs Work.” The lecturers are Mr. Yoshiaki Nishimura (working methods researcher / Living World representative) and Mr. Tsukasa Mori (Section Chief, Tokyo Culture Creation Project, Regional Cultural Exchange Section, Tokyo Metropolitan Foundation for History and Culture). With the Foundation Courses coming to a close, from here on the TOBIRA candidates (hereinafter called “TOBIKO”) will see how they can actually work in the setting of the Tokyo Metropolitan Art Museum (hereinafter called “TOBI”). This course was held for that possibility and preparation.

At first, Mr. Nishimura put forward the theme of “The TOBI Gateway Project and Who I Am Now.” When the Course participants became TOBIKOs, they became quite familiar with TOBI and developed bonds with other TOBIKOs. Different plans began to sprout, and he has begun to realize the great expectations and challenges of conduct for TOBIKOs. To look back a little on the present, the TOBIKOs paired up and discussed their recent circumstances. Of course, the most important issue was “listening ability.” Mr. Nishimura once again advised that “listening ability” means “truly having an interest and concern in that person.”

After that, Mr. Nishimura spoke about “the style of not prioritizing the mission, but whoever happens to be there is everything” with the example of a talk by Mr. Hideki Toshima (originally at Graph) who he met at a lecture titled “3 Days to Think about one’s Work” (2009). He worked on such projects as the installation design of Mr. Yoshitomo Nara’s works, and he said that the design company Graph, performing on a global stage, was started by 6 friends who gathered together with their canned coffee drinks on the stone steps of the Nakanoshima Public Hall in Osaka. At that time, people such as half craftsmen or cooks gathered after work to talk about the current circumstances of such things as each other’s dreams and work. In that situation, one of the members made a chair, and at that point Graph’s activities started to move. Graph grew rapidly with the chain of ideas “If you can make a chair, I’ll go sell it. If we can sell it, we’ll need mass production and that will require a studio, right? If so, then let’s rent a building, then we can make a showroom, then I will have a café there.” They didn’t decide on their mission and goals and then recruit the people with the necessary abilities, but potential sprouted from the people who happened to be there. This vague method of sharing things like each other’s dreams and potential to find the shape of the future by thinking “it’s something like this” is “the style of not prioritizing the mission, but whoever happens to be there is everything.”

This “the style of not prioritizing the mission, but whoever happens to be there is everything” is the actual common point with the “day after tomorrow potential” that the TOBI Gateway Project envisions. (For more about “day after tomorrow potential,” please refer to “Educe cafe: Bringing out the Community through Art” that took place on June 6th at The University of Tokyo.) I want the TOBI Gateway Project to take great care of the various faces that gather at TOBI and the vague image of the future arising from accumulating achievements which are only possible at TOBI.

To tell the truth, the image of the activities for the TOBIRA Gateway Project wasn’t firmed up when planning began. Not even the curator, Ms. Inaniwa, myself (I really hadn’t even dreamed that I would be the Project Manager) or any of the instructors had even imagined anything at this time last year. However, we met, spoke with and shared feelings with people, we thought and became impassioned, and bit by bit, we built the principles and direction of the TOBI Gateway Project. It can really be said that the form of this TOBI Gateway Project came about exactly because of the staff that we have. So I want to have the same stance in connecting with the objective of TOBIRA activities.

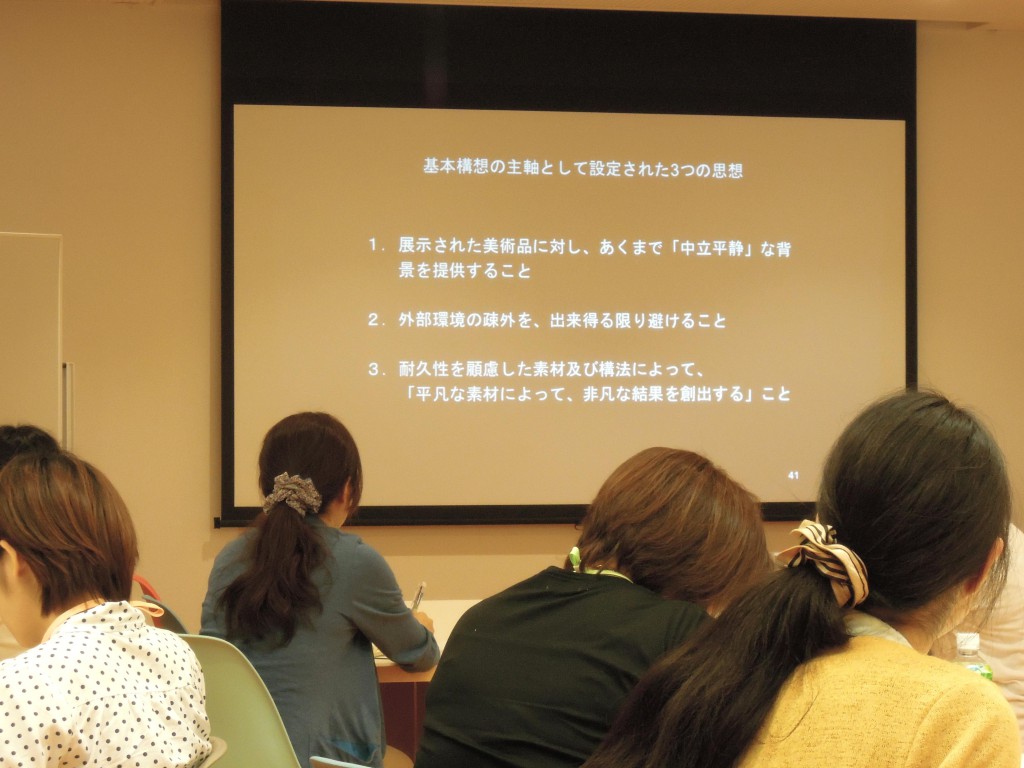

Whether these thoughts were certainly included or not (I’m not sure), Mr. Nishimura next instructed us to make groups of three people from the members gathered here and for those people to think of unique ideas. He said that the image of the smallest social unit is three people in a group. They soon made groups of three people and began with each person writing in a notebook “what I can do,” “what I’m not bad at” and “what I’d like to try sometime.” After writing in the notebooks, they chose just one of those words and wrote it on post-it notes that were distributed.

They showed each other the post-it notes with the words they chose, and the three members thought of an idea from those three words. At first, they came up with ideas unrestrained by the place called “TOBI.” Since they came here, this was the first time they realized that the other TOBIRA candidates had unexpected special skills that were many hidden hints which may be useful in future activities.

After the three members tried once to form a simple planning idea, they then continued deepening the image. Next time, these three will think about what they can do at TOBI. While discussing what they themselves can do in the setting of TOBI bringing their three words, the morning ended. Each group was then assigned homework to submit their plans on one A4 sheet of paper by the afternoon, and an active meeting continued even into the lunch break.

Lunch break ended and the afternoon session started. Mr. Mori joined and checked each of the plans. With Ms. Shiomi, (“I want to go skydiving”), Ms. Komatsu (“I want to travel all over Japan”) and Ms. Hirano (“I want to be in the newspaper for something other than a bad thing”), it was like “TOBIRAs jumping out of the sky.” (Laughs) “TOBIRAs will skydive into all parts of Japan. We will have the letters ‘TOBI’ written on the parachutes. We will take pictures where we land and display them at TOBI.” There’s no way that will work. Other than that, a lot of unique ideas like a “night museum” and “Roaming around and cleaning TOBI” came about.

Mr. Mori provided severe and pertinent advice combining both realistic and not realistic ideas such as “Planning means that, even while you are expanding an image based upon many ideas, you should be taking it down into a simpler action plan” and “an itemized plan just consisting of a list of everyone’s ideas isn’t called planning.”

After comments on the planning reports had once finished, Mr. Mori said the sharp comment: “A lot of ideas emerged, but from here the problem is who exactly is going to carry them out?” Then, the expectations of TOBIRAs were expressed with the term of a “new public commons1.”

As my own little addition to “new public commons,” in the 1980s based on the thought that the town would become cultural if you made a cultural facility, there was a period called “box (building) administration (public policy focusing on the construction of public buildings)” that built the many community centers and halls. There were certain expectations such as: if you build the box, people will come and cultural activities will develop; if cultural activities occur, the effects will spread to the facility’s surrounding areas and there will be flowers and sculptures. But this didn’t happen at all. How do you use a multipurpose facility that anyone can use? They became places with no clear purpose and were even derided as “places with luxurious chandeliers completely lacking in exuberance.” The root cause of this failure lies in the idea that, “if you have the “hard,” the “soft” will naturally occur. Then, when it became clear that the energy of activities lies not in the buildings but in people, the Japanese economy fell into a decline with the collapse of the economic bubble. Ultimately, even if you make the “box,” there is no meaning if you don’t think about the contents. Rather, if you have the contents, there were claims that the “box” could depend on ingenuity. As a result, the era has been shifting “from “boxes” to people” and from “hard to soft” (because this is the time of art projects being developed in the middle of communities). The thought until now that the role of profit return to communities with boxes should now be entrusted to people and not a box is included in the term “new public commons.”

However, there is the question of “What will TOBIRAs do as the bearer of this “new public commons?” I am forced to think deeply about this as the Project Manager. When I looked from the perspective of a place to actually carry out a project, the extremely difficult point was that an actionable “plan” and an “idea” are clearly different. This is just my interpretation, but I think that “plan” can mean “strategy.” I mean, this is finding a path while making an overview of the expected future. If you have this image (even if its vague), even if things happen like you fail along the way or your actions don’t go well, you will accumulate these as results. But the failures and actions of your ad-hoc “thoughts” can easily produce discouragement and despair. You can’t waste the energy that you’ve worked so hard to store up. This is because “ideas” will go no farther than the “strategy” of doing something to the scene right in front of you. It’s difficult to have a bird’s eye view. Therefore, repeating “strategies” (ideas) without grand “strategies” (plans) will lead to extremely dangerous acts in running a project.

I think probably a general way to avoid this is to gather at the progress stage of the project and present the common “strategies” (plans) of all members each time and then proceed with an appropriate division of roles. However, I dare to say that in the TOBI Gateway Project I’m thinking of not doing that. This is also one of the challenges of the TOBI Gateway Project. Even regarding the “strategy” (plan), for example, if it were me, I would think at what step we could continue growing the TOBI Gateway Project. About all of the TOBIKO, I don’t necessarily think they all have to share one common thought about what kind of self-realization is possible and what they should do now toward that end. It’s important for each of them to find their own “path” (strategy) in their own motivation. Without deciding a permanent division of roles to build an organization, I want an organic team assembly progressively structured by the TOBIRAs, each with their own “strategy” (plan), to be able to continue painting an overview of the TOBI Gateway Project. I know that the obstacles are quite high, but Mr. Mori and Mr. Nishimura have said in their talks that “TOBIRAs are each a ‘one-man business.’” That’s exactly what I think, too. TOBIRAs aren’t volunteers in given roles.

A “new public commons” does not simply mean volunteers working. It calls into question each individual’s maturity and experience, and a very high level of performance is expected. Those that can become the “new public commons” will be the centrifugal force of activity woven into the TOBI Gateway Project. That is the great expectation of the project which I would like the TOBIKO to really feel.

Also, with these great expectations, the question of “What do you do next?” has been posed to the TOBIKO.

Again, with renewed feeling, we rearranged the groups of three and began talking about “What do you do next?” When thinking about the ideas of “the style of not prioritizing the mission, but whoever happens to be there is everything” and “new public commons” each being the working methods of TOBIRAs, this becomes a very important theme. There was something much deeper than originally expected in the message in the issue of “What do you do next?”

There was a submission regarding this issue not during the Foundation Course, but written on the “Message Board for TOBIRAs.” (I apologize that I cannot give those other than TOBIKOs reading this blog access to this board.…). From here, I plan to progress toward realizing that which seems capable of realization.

—I think there may be a steep road ahead toward the high ideals of the TOBI Gateway Project. With these TOBIKOs, I believe these ideals certainly can be realized. Also, aside from the staff who frequently appears in this blog, there are also staff who work hard supporting the TOBI Gateway Project. From the left, there is Ms. Manabe, our intern, Mrs. Kondo, our coordinator, Ms. Kumagaya, our part time worker, and the curator, Ms. Ohashi (in charge of the The Royal Picture Gallery Mauritshuis (Maurice House) exhibition!). (Sorry if the photo is a bit blurry.) Unfortunately, Mr. Otani, our assistant, isn’t in the picture. He’ll be there next time. Even for “the style of not prioritizing the mission, but whoever happens to be there is everything,” I think we have a great group. (Ito)

“New Public Commons” (「新しい公共」)is an idea, under which not only the government but also citizens, NPOs, private businesses, and other parties, with the spirit of mutual assistance, play an active role in providing services for our everyday life such as education, childcare, community development, nursing care and welfare services. Available at http://www5.cao.go.jp/npc/index-e/index-e.html.

2012.06.09

はじめに、西村さんから出されたテーマは「とびらプロジェクトと自分の今日この頃」。とびコーさんとなって、都美にもだいぶ馴染み、同期のとびコーさんとも仲良くなってきた今日この頃。いろいろな企画の芽も出はじめ、周囲から寄せられるとびコーさんへの期待の大きさと、振る舞いの難しさにも気付きはじめ今日この頃。少し今を振り返るために、ペアになって近況を話し合いました。もちろん大事なのは「きく力」です。西村さんからは改めて、「きく力」とは「本気でその人に興味や感心を持つこと」とのアドバイスもありました。

各々選んだ言葉が書かれたポストイットを見せ合い、3つの言葉からイメージできる、3人ならではのアイディアを考えます。はじめは特に都美という場所に捕われず、アイディアを出し合いました。ここに来てはじめて、とびコーさん同士の意外な特技に気付く事も有り、今後の活動に役立つヒントが多く隠されていることが分かりました。

企画の簡単なアイディアを3人で一度つくってみたところで、さらにイメージを深めて行きます。今度は、この3人で都美でできることは何かを考えます。3人で3つの言葉を持ち寄って、都美を舞台に、ここにいるメンバーだからこそ出来ることはなにかを話し合いながら、午前中は終了。午後までに、グループごとにA4用紙1枚に企画をまとめて提出する宿題が出され、お昼休みも活発なミーティングが続きました。

とびらプロジェクトの理想は高く険しい道のりの先にあるのかもしれませんが、きっとこのとびコーさんたちとなら、実現できると信じています。そして、ちょいちょいブログに登場するスタッフの他にも、とびらプロジェクトをしっかりと支えてくれているスタッフがいます。左から順に、インターンの真砂さん、コーディネータの近藤さん、アルバイトの熊谷さん、学芸員(マウリッツ美術館展担当!)の大橋さん。(ちょっとピンぼけしていてすみません。。。) アシスタントの大谷さんが写ってないのが残念。今度登場しますね。「ミッション先行ではなく、居合わせた人がすべて式」にしても、よくぞ集まったと思います。(伊藤)

2012.06.06

稲庭さんのトークが終わるとしばし歓談。お酒や食べ物などをご用意頂いており、周囲の方々とご挨拶やお話をさせて頂きました。今回会場に集まった方々は、東大の学生さんだけではなく、アーティストや一般企業・NPOで働く方々など幅広く、大変有意義なひと時を過ごすことが出来ました。

2012.06.06

Curator Sawako Inaniwa (Chief for Education and Public Programs, Tokyo Metropolitan Art Museum) was invited as a guest speaker for “Educe Cafe” held at Fukutake Hall at The University of Tokyo to give a talk about “Bringing out the Community through Art.” Of course, I attended the event, along with Ms. Kondō (TOBI Gateway Project Coordinator), Ms. Ōtani (TOBI Gateway Project Assistant), and the TOBIRA candidates (hereinafter “TOBIKO”).

Being the fan that I am, I was deeply impressed with the beauty and spaciousness of The University of Tokyo campus.)

To break down the theme “Bringing out the Community through Art,” the following two questions arose: “What is the role of art in the formation of communities?” and “What kind of possible approaches could museums take to achieve them? “ These questions speak to challenges we face following the renewal of the Tokyo Metropolitan Art Museum (hereinafter “TOBI”).

First, Ms. Inaniwa analyzed the factors in creating a community in the Matsuba district of the Daito Ward where she resides: space, layers of time, the presence of introspective events and objects, places to practice, places of collective study, and sacred places. With this in mind, she explained the possibility of forming communities using museums as a social device when comparing the roles and functionality of both local museums and temples.

While using Ms. Inaniwa’s talk as a base, my impression is that, while temples and shrines are all part of our daily lives, they still can create an “extraordinary space” and be deep-rooted in people’s lives. Although I personally don’t have any specific religious beliefs, I feel like my body and soul are purified when walking through shrine or temple gates. In addition, temples and shrines are normally very quiet, but when there are festivals, tons of locals get together and even I have a great time. While Buddha and God have a special intangible existence to the locals, we incorporate them into our lives and live together in harmony.

I felt that having a fine line between an extraordinary and an ordinary space is quite important to creating a vivacious community.

These kinds of human interaction represent the ideal image of community-based museums that the TOBI aspires to be. For example: museums are also usually quiet (despite the fact that the TOBI is almost never quiet…); art exhibitions are in the back with a slightly higher threshold. Once you do go inside, there is a sense of tension to remain silent. However, when you have had a chance to unite with the locals, you can share the power of the museum with a variety of people. And I hope that TOBI can become the type of intimate museum where the locals can think “This is our museum.”

The main functions of a museum revolve around things like art collections, research, and holding exhibitions. Making these roles clear allows the museum to function as a social device where people become unified with the museum. However, for better or for worse, TOBI does not have its own art collection. (To be precise, they do actually have a small collection.) Exhibitions displayed at TOBI change on a regular basis depending on our projects. A wide variety of exhibits are held here, from large exhibitions like “Masterpieces from the Royal Picture Gallery Mauritshuis (Maurice House)” and “Earth, Sea, and Sky: Nature in Western Art; Masterpieces from the Metropolitan Museum of Art” to small amateur artists’ public exhibitions. Even though TOBI does not have a collection of art works, art becomes the conduit for connecting a variety of people, such as: people who come to see the exhibits, people who submit their pieces to public exhibitions, instructors and students from the Tokyo University of the Arts located right next to the museum, and people who are taking a walk in Ueno Park and then have lunch at the TOBI restaurant. TOBI should take this chance and use the “art communicators” (TOBIRAs) to make new connections with as many people as possible, and use the energy that museums have to become the “driving force” behind giving back to the community and society. I realized after the talk that, in order to achieve this, we need to let the TOBI Gateway Project grow in hopes that the TOBIKOs will nurture the feeling of the TOBI being their museum. In order to do this, after Ms. Inaniwa’s talk, I realized that we first need to help make the TOBIKOs feel like TOBI is their museum and ensure that the TOBI Gateway Project is a success.

After Ms. Inaniwa’s talk, it was a time to mingle. Food and drinks were provided, and people socialized with others. People who attended the talk were not only students from The University of Tokyo, but also included wide variety of people such as artists and people who work for companies and non-profit organizations, all of whom seemed to have a meaningful time here.

The second half of the event was a time for questions and conversation. We began by discussing the future direction and development of the TOBI Gateway Project after the museum’s impending renovation; we had a heated discussion about the relationship between art and community from various points of view. There was a specific focus of the discussion was on how people envisioned the TOBI Gateway Project reaching its goals, and the answer was the “day after tomorrow potential.” I got to speak up a little during the discussion. The “day after tomorrow potential” is explained as a “vague image of the future,” as cited by the words of Mr. Kiyokazu Washida in the “100 nin-de-kataru-bijutsukan-no-mirai (Discussion on the Future of Museums with 100 People” (Keio University Press, 2011). In comparison, the image of “tomorrow” is a “future that already has determined goals.” In order to achieve the envisioned results of “tomorrow,” you will define the tasks, put them into your calendar, and execute them. It is a method of creating an image of the future calculating backwards from set goals to figure out the steps to achieve them. Perhaps the majority of people live their daily lives using this “tomorrow” image method. (I am usually one of them, too.)

However, the “day after tomorrow” in this context is an image of the future which exists beyond tomorrow, unlike “tomorrow”, which is a nearby future. I have already described above what the “day after tomorrow” image that TOBI is aiming for. But rather than calculating backwards what is necessary to achieve these goals, the TOBI Gateway Projects’ goal of the “day after tomorrow” image is achieved by accumulating the experience that can only be accrued from those various people who come to the museum. At one point, there was a time the TOBIKOs introduced themselves in front of everyone, and each of them shared their thoughts from the point of view on becoming successful art communicators in the future. Having an interested party like the TOBIKOs at the talk allowed the discussion to become more intriguing and deep.

When I think of it, the TOBIKOs include people aged from their teens to their 70s. They included a wide variety of 90 unique members such as: students, company workers, housewives, retirees, researchers, nurses, teachers, reporters, artists, city council ward members, quiz authors, etc. Is there any other platform where people with such diverse backgrounds, generations, and values can interact so equally other than the arts? (Even as I write this, I am impressed at how these people all gathered here together.) The TOBI Gateway Project is a place where a wide variety of people come together, share goals for the project, and even sometimes engage in debates, while always respecting each others’ individuality to create a community with new values. (Ito)